From Monday to Thursday, primary school teacher Stephanie Castella teaches Years 1 and 2.

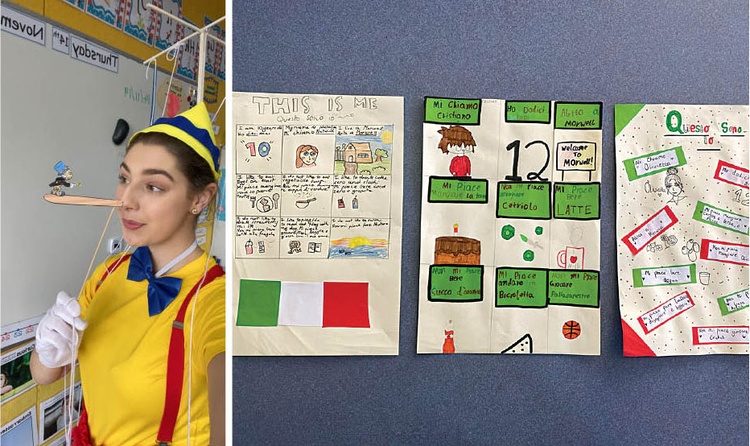

On Fridays, Castello transforms into the school’s Italian teacher, welcoming students from Year 1 to Year 6 into her classroom.

Two years ago, the St Vincent de Paul School adopted the Autonomous Language Learning (ALL) approach to teaching Italian.

Castello underwent a training course to fully understand this method, which provides students with the opportunity to practise authentic conversations, as opposed to scripted textbook phrases.

“I don’t want to only focus on themes such as days of the week, numbers or colours,” Castello explains.

“I want my students to learn how to express themselves in Italian and to feel comfortable when they speak.

“This approach guarantees students real opportunities to practise the language through conversation.”

Through the ALL method, teachers identify 100 words for children to learn each year, aiming for 25 a term.

Teachers utilise different techniques, such as role-playing and classroom conversation.

These methods help students to memorise the words and use them in various phrases.

“Teaching high frequency words is one of the strategies of the ALL approach,” Castello says.

“The Italian words I want the students to learn are repeated in class and are always accompanied by a gesture.

“This way, the children make a mental connection between the gesture and the word, which is a very effective tool for memorisation.

“This is a particularly useful method when teaching younger students.”

Castello organises games where the current set of words-to-be-memorised are at the heart of the activity.

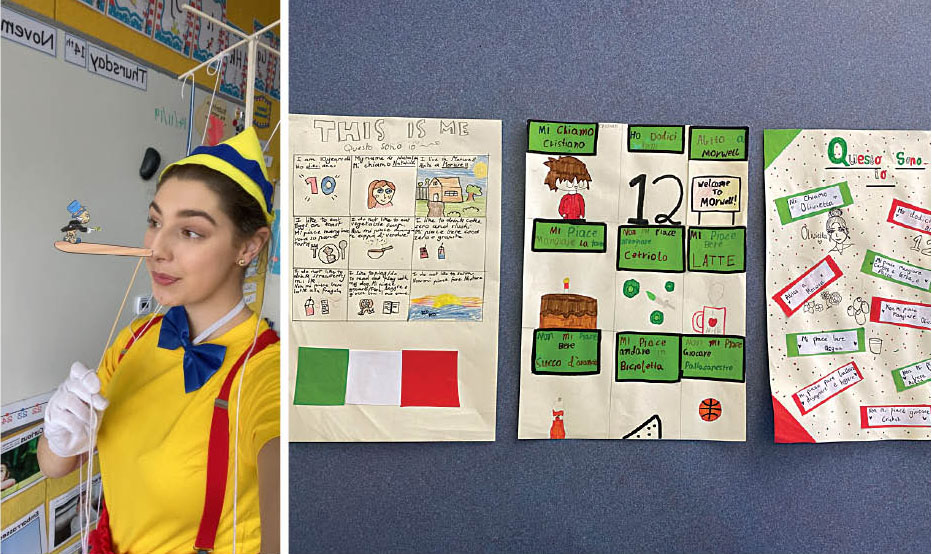

“We work on sentence construction,” she says.

“I often change the order of the words and the children have to put them back together so that the phrases are correct.”

The goal of the ALL method is to build students’ confidence, so that the children feel safe when they speak and have the ability to ask questions in specific situations, such as requesting information or permission.

Morwell students are also free to express themselves in class, creating posters that detail their likes and dislikes, along with basic information about themselves.

According to Castello, involving the students and making lessons fun are key.

Each week, she chooses two students to entrust with a special role by handing them a tag affixed to a lanyard that they can wear.

One student becomes the teacher’s “assistant”, who helps Castello demonstrate activities to the rest of the class, pairing up with the teacher for conversations and role-playing games.

The second student becomes the classroom’s “policeman”, whose job it is to check if his classmates are paying attention in class.

If the “policeman’s” peers are not behaving as they should, the student may issue Italian admonishments to those who are distracted or not participating.

“The students enjoy having a role during their lessons,” Castello explains.

“It works especially well with the little ones, Year 4 and under.”

The teacher creates incentives for her students to use Italian, such as the “pasta jar”.

Every time a student says something in Italian to their teacher or a classmate, they can put a piece of pasta in the jar.

Once the jar is full, the students receive their prize.

“Last year, when a class filled their jar, we went and bought gelato for everyone,” Castello says.

“When the students make a mistake while speaking, I encourage them to try again, because it’s the only way to succeed.”

Castello grew up speaking Italian with her parents and studied the language all the way through her education.

Her father was born in the Sicilian town of Vizzini and her mother in Foggia, in Puglia

After high school, she enrolled in the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, where she studied for two years.

In addition to her studies, she obtained a qualification to teach Italian; then spent several months in Rome as an au pair, chasing her love of the language – a passion that has continued to burn.