However, where once she rebelled against the traditions of her Italian family culture, she now nurtures her heritage and encourages her own children to take full advantage of being bi-cultural.

Lucy’s story is likely to resonate with many of the readers who have found themselves, as children and grandchildren of migrants, caught between two worlds. Whilst the story may be common, the experience is deeply personal. The personal story is found in how each individual navigates the two worlds, especially given the complexity of life which invariably unfolds in a different way for each person. This is Lucy Cirocco’s story, and that of her family.

Lucy’s parents migrated from Molinara, famous for its grape variety of the same name. Their quest was to have a better life. A chance to work, put food on the table, raise their children and provide them with opportunities such as schooling, which was otherwise impossible to achieve.

Molinara, in the commune of Benevento, is not far from Naples, but it is very far from Adelaide, the place where Lucy Cirocco’s parents migrated separately. In the game of distance and migration strange things happen. As fate dictated, the two migrants from Molinara met in Adelaide.

Lucy’s mother, Cristina Spagnoletti, came out with her mother and younger sister Caterina. Cristina’s father had come out a few years earlier to organise work and establish himself before arranging for his wife and young daughters to join him. Cristina was only nine years of age at the time. The story is a common one for those who arrived in the post-war period to Australia. Lucy’s maternal nonni worked hard, built a house and settled into the community to raise their family.

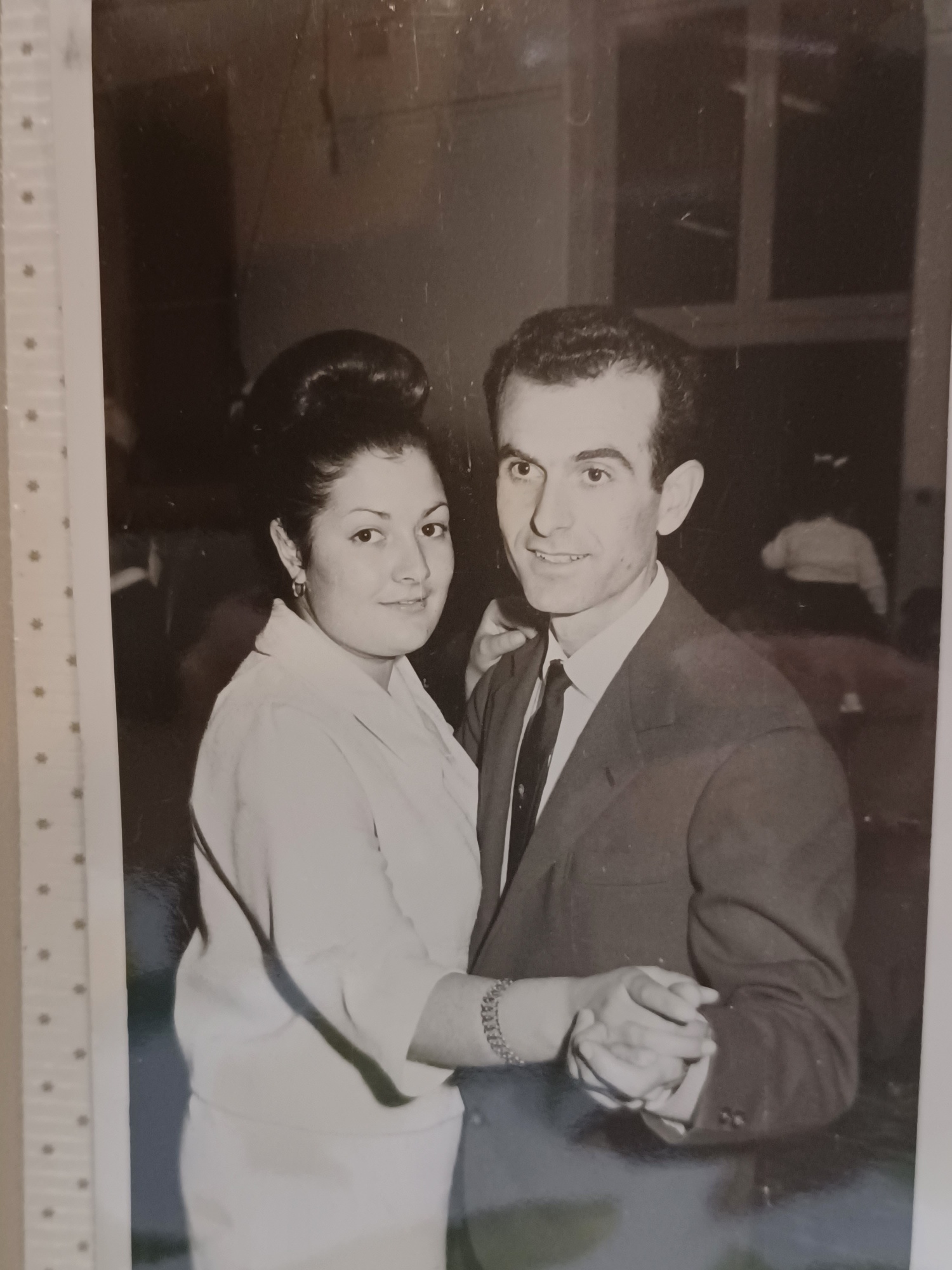

Coincidently, next door lived another family from Molinara. One particular day, Rocco Cirocco turned up there with his suitcase ready to give Australia a go. This is how Rocco and Cristina met. It turned out that shy glances over the fence led to romance and the rest is Cirocco- Spagnoletti history.

Cristina Spagnoletti and Rocco Cirocco at a dinner dance (1963)

Lucy is realistic about her upbringing and her family’s migrant experiences:

There were tough times. We were outsiders and through the racism we experienced, we were constantly reminded that we did not fit into society. At times we felt we were barely tolerated. This meant that traditions were maintained rigidly in our own household, a sort of protection mechanism. We felt we almost had two different identities just to survive. An Italian identity, and the one we put on when we went outside.

The need for connection and belonging for the family meant that paesani came together to form a mini community. People were called zia and zio without really being an aunt or uncle. They took the place of the extended family which was important to new migrants.

Recipes were swapped during community picnics, men would chat during card nights, and when the Molinara Club was established, dinner dances were held where young adults could court under the watchful gaze of every older person in the community.

We did not live the same lives as our non-Italian friends. Our family values were different, so too was our family makeup. My nonni even lived between us and my father’s brother. Our nonni were brought out in the early 60s to ensure the family stayed together. Everything about us was different.

Families lived together, played together and shared everything, including gossip.

For Lucy, there was a period as a young adult when it was all too much. She wanted what her non-Italian friends had. Permission to go to sleepover parties, curfew-less Saturday nights and freedome from the watchful and critical eyes of her extended family. She yearned to be liberated from the pressure of academic study and to look forward to an alternative life than that which conformed to the notion of casa e chiesa (home and church) for a woman.

The world called Lucy, and it was a different world to that of her parents.

Lucy explains her philosophy on the experience of being part of the Italian diaspora of her time as being bound by the “Italian holy trinity: Guilt, Shame and Obligation.”

So, what does a young woman do? She rebels.

Lucy dropped out of university in favour of a steady income and sense of freedom. She sought out friends beyond the usual sphere and she became increasingly curious about the wider world. However, her family’s mantra of being of service and contributing to the community was a strong thread in her life. For many years Lucy worked in the area of rape and sexual assault services, as well as in child protection.

As she navigated life, she found that the values instilled by her parents contributed to the choices she made in shaping her future. She found herself back at university as a mature-aged student. This time she was focussed on her own educational choices.

As a young mother, Lucy reflected on and explored aspects of culture which she felt were important in defining a culturally rich life for her own family. After all, with an Anglo-Australian husband, there was another diaspora culture to consider. She had developed a sense of balance between the two cultures which defined her and understood the importance of supporting her own daughters’ development of a healthy pluri-cultural identity.

The young sisters Lilah and Scarlett at the San Rocco Festival, Molinara (2014)

For Lucy, the power of community connection and identity are both important:

…but these cannot be imposed. Expectations to conform can be overwhelming. Instead, it is important to personally take up responsibility to engage with others in a meaningful way – not because you must but because you want to. This is important to establishing your sense of identity in any group.

Where there was once some uncertainty around navigating the third space between being Italian and being Australian, Lucy found clarity. She and her family have enjoyed the best of plurilingual, pluricultural worlds.

Having a strong sense of family has proven to be the foundational value for Lucy and her family. This means that they all congregate at nonna’s house for Sunday dinner. Certain foods are prepared and served in specific ways to mark significant occasions. Rituals around baptisms, weddings and grieving are all maintained by the family.

There was a particularly moving moment during Lucy and Dan’s wedding reception which expressed the family’s openness to the richness of diversity. The wedding was held with guests representing various cultures brought together by the occasion. Sadly, Lucy’s father passed not long before her wedding to Dan Cox, whose own father migrated from England. It meant that tradition was broken in some significant ways, for instance, it was Lucy’s mother who walked her down the aisle.

Yet there was not a dry eye at the reception when Dan’s father, stepped up to make his speech. To the surprise of all, he honoured the memory of Lucy’s father, Rocco, by delivering the speech in Italian. He had practised the speech in secret with an Italian work colleague just for the occasion.

This very moving moment transcended diversity and unified everyone. It was representative of the unique space that is created by migrants as they navigate their hybrid identities, their sense of place and what they then choose to create and engage with around them.

For Lucy, and Dan, their own strong sense of place ensures the next generation remains strong in its acceptance and enjoyment with their own pluri-cultural sense of identity. Their daughters, Lilah and Scarlett, embrace their heritage wholeheartedly. They are both Italian citizens, have travelled to Molinara to meet their cousins, and one even has a tattoo of the settebello (the luckiest card in the Neapolitan deck of cards when playing the popular game of Scopa).

Lucy laughs when she thinks of her own experiences, “I was like a bridge between two generations, two languages, two cultures, two worlds.” She hesitates for a moment before speaking again, “So much for rebelling.”

This article is the first in a series in which we meet individuals who tell us their story of being Italian+, that is, being pluri-cultural.