The boilers are turned on and the machines are sterilised.

At 4:00 am, the pasteurisation process begins.

Once the milk is pasteurised, enzymes are added to aid the fermentation and coagulation processes needed to obtain the whey (used to make ricotta) and curd.

At 6:00 am, the real magic begins and the cheese is made.

At 8:30 am, when most of us are starting our day, mozzarella starts being worked at the Floridia factory, in Thomastown.

After the stretching and salting phases, the mozzarella is ready to be packaged at 1:00 pm.

The next step is up to us as consumers... How will we choose to use these soft and creamy balls of goodness in our kitchens?

The rigorous hours of the dairy industry don’t seem to bother the third generation of the Montalto family, who are now at the helm of Floridia Cheese, founded in 1955 by Mauro and Carmela Montalto.

“This has been my life since I was born,” says Rose Portella, daughter of Tommaso (Tom), the Montaltos’ second-born child who was handed down the business by his parents.

“The same goes for my siblings Lisa, Mauro and Daniel.

“Floridia has immense sentimental value for us.”

The three generations all lived under the same roof in Bundoora, on a 30-acre piece of land which was home to Floridia’s first factory.

“I spent the school holidays making trecce and mozzarella,” Rose recounts.

“I could see my parents and grandparents at any time of the day... It was like living on a farm.”

Her husband, Fabio Portella, has also been a part of the family business for around 30 years and is now production manager.

“I remember when the family came together for dinner, the conversation would always turn to cheese,” Rose adds.

“My grandfather was a shepherd boy in Sicily, before he migrated.”

Mauro Montalto arrived in Melbourne in the early 1950s, followed shortly by his wife Carmela and their three sons.

They settled in North Melbourne and soon began making ricotta in the backyard.

They made it the old way: in a large cauldron hanging over a fire and using the rennet extracted from lamb’s stomach.

This ancient method doesn’t require enzymes because in those days milk wasn’t pasteurised.

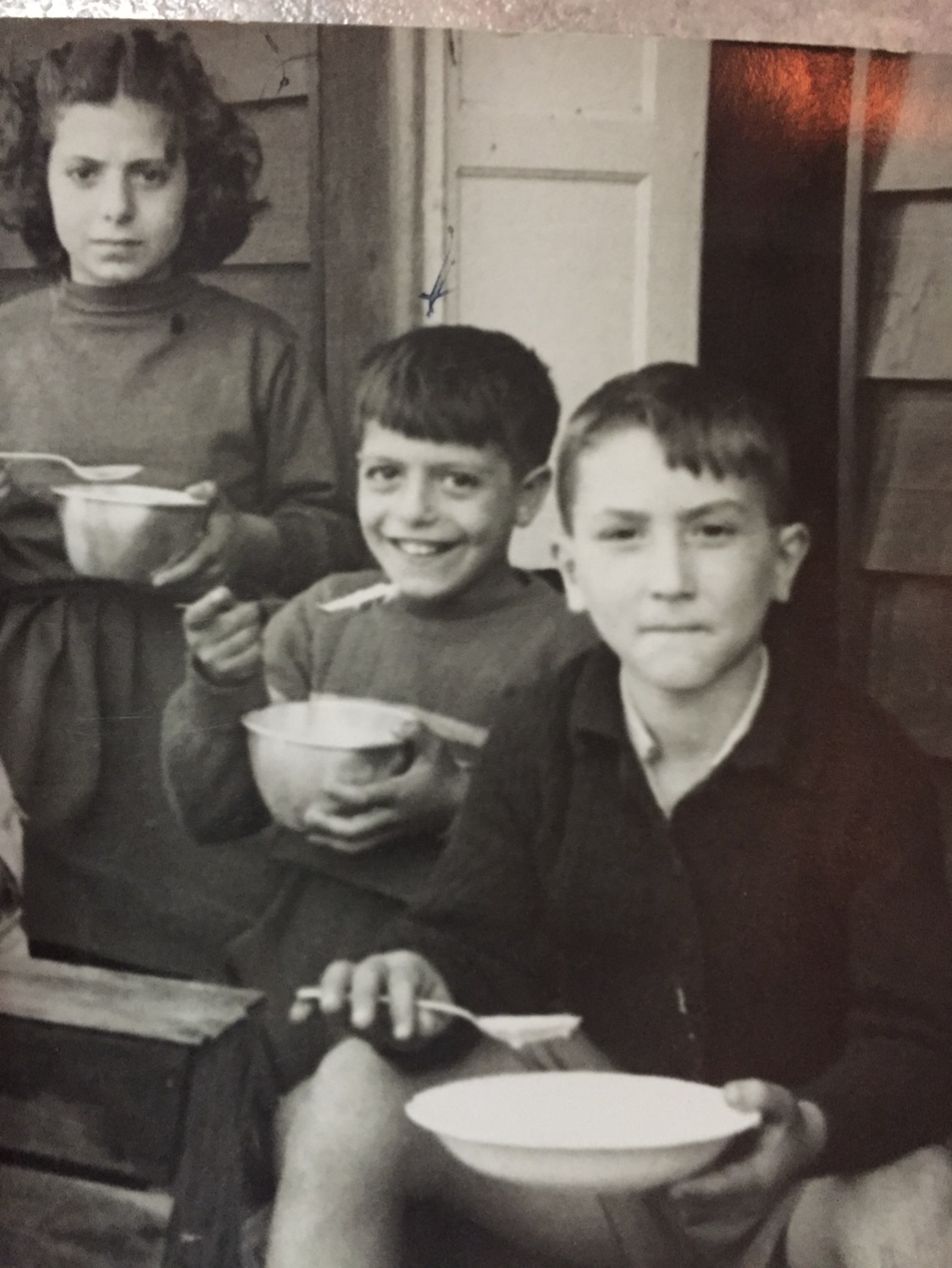

Tommaso Montalto (front) and two neighbourhood friends eating his parents’ ricotta

The Montaltos needed to feed three children.

Then, their neighbours’ kids too.

Eventually, they were feeding the entire neighbourhood and a growing Italian community.

Carmela walked around door-to-door selling their ricotta.

Unlike her husband, she could read and write, and she always carried a chart with her, where her Australian friends had noted down the numbers in English for her to refer to for receipts.

When they moved to Bundoora in 1955, it was Carmela who made the deliveries to Melbourne three times a day.

Meanwhile, Mauro often worked double shifts, sleeping on a piece of cardboard on the factory floor for a couple of hours in between.

Before more mechanised systems came about, this was the only way to respond to the growing demand for their products.

The Montalto boys went to the best schools in Melbourne (one actually was boarding in Geelong), to get the education their parents never had access to.

Tom was 15 or 16 when he realised just how much his father bent over backwards to keep the company going, and the teen decided to drop out of boarding school to help out with the business.

In the late 1960s, Mauro bought some land in Whittlesea, where he bred cows, sheep and pigs.

When he wasn’t in the factory, he was on the farm; even his hobby was work.

According to Rose, the farm was a way in which Mauro could return to his Sicilian roots and his childhood as a shepherd.

It was impossible for Mauro to visit Italy for a real holiday.

“You can’t close a dairy factory,” Rose explains.

“The cows don’t go on holiday and the milk has to be delivered every day.”

Rose’s voice is full of emotion when she talks about Mauro and Carmela, who passed away six and three years ago respectively.

“They were both very affectionate and present, but my grandfather would throw himself on the carpet to play with us and our children,” she says.

“He had a great sense of humour and he loved to go and dance on a Saturday night at the Floridia Social Club.

“Every year for Easter Monday, it was the club which came to us in Bundoora: there’d already be 200 cars parked at the factory in the morning, and they all came to eat the ricotta while it was still hot.

“In the afternoon, they’d light up the barbecues.”

In 1999, the factory moved to its current location in Thomastown.

The company now has around 80 employees who help to produce 50 tonnes of cheese a week.

While the Easter Monday celebrations no longer take place at the factory, community members young and old still head along for a taste of the hot ricotta.

While Floridia still uses original recipes, the production techniques are always evolving.

“We frequently travel to Italy to study the latest technologies, machinery and ingredients, like enzymes,” Fabio says.

“Meanwhile, we go to Germany for packaging equipment.

“Nowadays we have to travel more and more often to keep up.”

As a family business, Fabio believes it’s easier to make decisions together and in a dynamic way to meet the changing needs of the market.

One example is creating a line of artisanal cheese to accompany products made with semi-automated processes.

Every day, Floridia’s refrigerated vans leave the factory on Settlement Road, carrying dozens of different products like small shops on wheels.

The main products are ricotta, mozzarella and pecorino.

At the Dairy Industry Australia Awards NSW, held in June, Floridia’s ricotta was once again awarded the title of Champion Soft Cheese.

The company’s semi-matured pecorino also wins many prestigious awards regularly.

Floridia Cheese has many projects on the horizon, which see it return to its roots in a way: the reduction of packaging and perhaps a section of the factory dedicated to products made with non-pasteurised milk.

Maybe the fourth generation of Montaltos will breathe life into these new ideas, sticking to the same recipe Mauro and Carmela brought to Australia from the old Sicilian village old Xiridia... better known as Floridia.