Built at the dawn of the first century AD when Augustus reigned over Rome, the great Roman temple of Cupra near Ascoli Piceno was, in the first phases of its existence, filled with colours and images in the third Pompeian style. It was adorned with the same hues and decorations that at the time were lavishly showcased in the richest homes of Rome and Pompeii.

This unexpected and extraordinary discovery has come from the Marche archaeological site, according to Naples University archaeologist Marco Giglio, where a mission by the Università Orientale, in collaboration with the superintendency and the town council of Cupra Marittima, which runs the Archaeological Park, has undertaken a new campaign of excavation.

“The temples with the inside of the cell decorated with paintings are extremely rare,” Giglio points out.” Up until today we had only known one in the III style, that of the Bona Dea (Good Goddess) at Ostia, where, however, the decorative style seemed much simpler, as well as the cryptoporticus of the shrine of Urbis Salvia (at modern Urbisaglia, near Macerata)”.

The scientific director of the digs, Fabrizio Pesando of the Orientale in Naples, goes on to explain, alongside Giglio, that in this corner of Marche, not far from the sea and a short way from where the Etruscans in the VI century BC successfully ran a shrine dedicated to commerce, the Romans had settled around 100 BC, with a ‘municipium’ that was then promoted to the rank of colony.

Inhabited by families of the armies of Mark Antony and Octavian and their descendants, Cupra, which had taken its name from the divinity of that temple (the historian Strabo says Cupra was another name for Hera), was a flourishing little town in those decades, with a forum and a large shrine, of which today there sadly remains very little, but which the excavations carried out by the Neapolitan mission in the last few weeks have enabled us to reconstruct to a certain degree. Or at least in its shape and in the two phases of its life, underscore Giglio and Pesando.

More or less 100 years after its foundation, around the first quarter of the II century AD, the temple showed grave static problems which made it indispensable to carry out a radical restoration, what the Romans called, an “a fundamentis” project.

This was a “major undertaking, and a costly one”, the archaeologists explain, carried out with the same advanced techniques that had been employed at Pompeii after the earthquake of 62 AD, the one which preceded Vesuvius’s fury by a few years.

It is for this reason that it is hypothesized that it may have been Hadrian himself who financed those works. Hadrian, who had been born in Spain granted, but who descended from a family from Atri, also in the Piceno area, and who in 127 AD took a tour of the area, stopping at Cupra.

It was during the reconstructions, the archaeologists today say, that the temple lost its magnificent original colours. This was because, having to reinforce the walls that contained the shrine’s cell, the wall coverings were chiselled off too and then in all probability covered in marble, as the fashion of the empire then imposed.

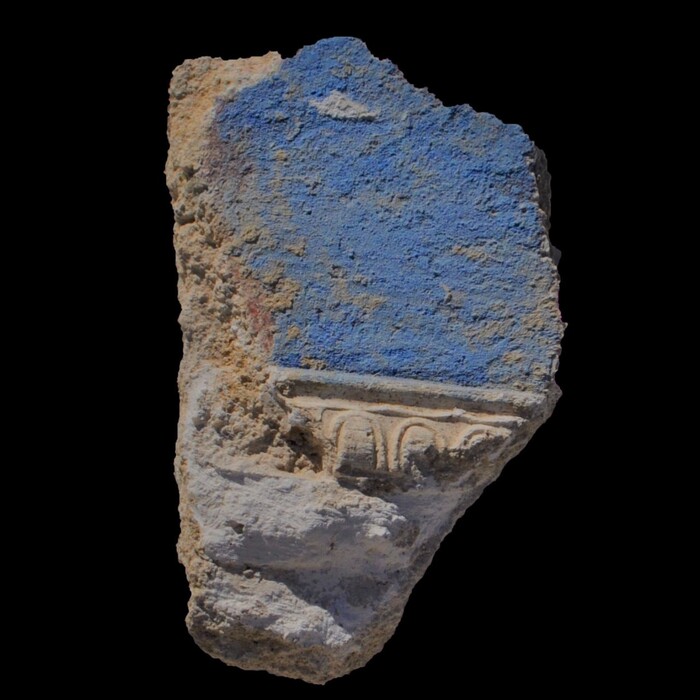

The marvellous sky blue, just like the yellows, greens, and reds which had illuminated that sacred space, ended up in a thousand pieces on the floor, which the Roman builders, who were used to recycling everything, went on to use as the base for the new floor.

The restored temple became a Corinthian hexastyle, with the six columns of the front that towered nine metres tall, decorated with rich capitals. But it was also embellished with a series of semi-columns in brickwork, which were placed onto the side walls, and dazzling lion-headed dripstones, which have also been brought to light by the recent digs.

It was a fresh wonder that Hadrian himself had conceived, as appears to be confirmed by an inscription found several years ago at nearby Grottamare.

This happened while building work was buzzing all over the city and monumental architecture was going up, including the two powerful brick arches which still today flank the perimeter of the temple.

And right in front of the staircase of the shrine, which is still preserved today, there rose the base for a celebratory monument, perhaps even a statue of the munificent emperor.

It is a shame that in the following centuries – when exactly this happened is still to be clarified – that all this beauty was dismantled. The precious marbles and imposing columns were reduced to lime to be re-used in other buildings, and even the walls of the temple, at the end of the 19th century, were knocked down to build a country house whose ruined remains loom over the ancient staircase of what was the Roman shrine.

“The park is weighing up whether to restore it or to remove it,” says Giglio. All the new finds, meanwhile, have been taken to restoration workshops where they will be cleaned and studied. The digs will resume in the spring and will this time focus, Giglio says, on both the two arches and on the back of the temple, in order to shed light on the decorations of its second phase.

Almost two thousand years after Emperor Hadrian’s, therefore, the Roman Cupra is also rediscovering, little by little, its rich history and its colours.