Born in Melbourne, Tartaglione found herself wondering what it truly means to be a migrant in modern Australia.

Constantly plagued by people demanding to know “where she came from”, and questions about the sacrifices of her predecessors, Tartaglione began to explore her family history.

“I regret not asking my parents questions about their lives and their history,” she says.

“I’m proud to be Italian and to have grown up in Australia, but I think that not having my grandparents, uncles or cousins around me had a profound impact on my life.”

Tragically, Tartaglione lost both of her parents at a young age: she was just 17 when her father died.

Aged 56, her father passed away in 1981, and her mother followed almost 16 years later, in 1997.

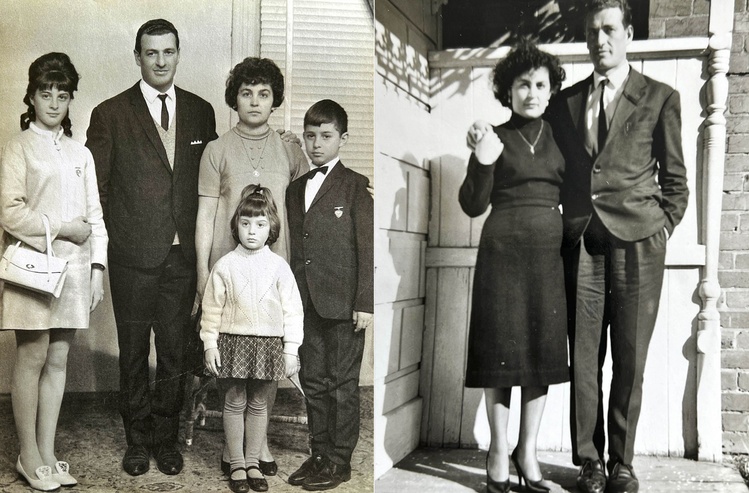

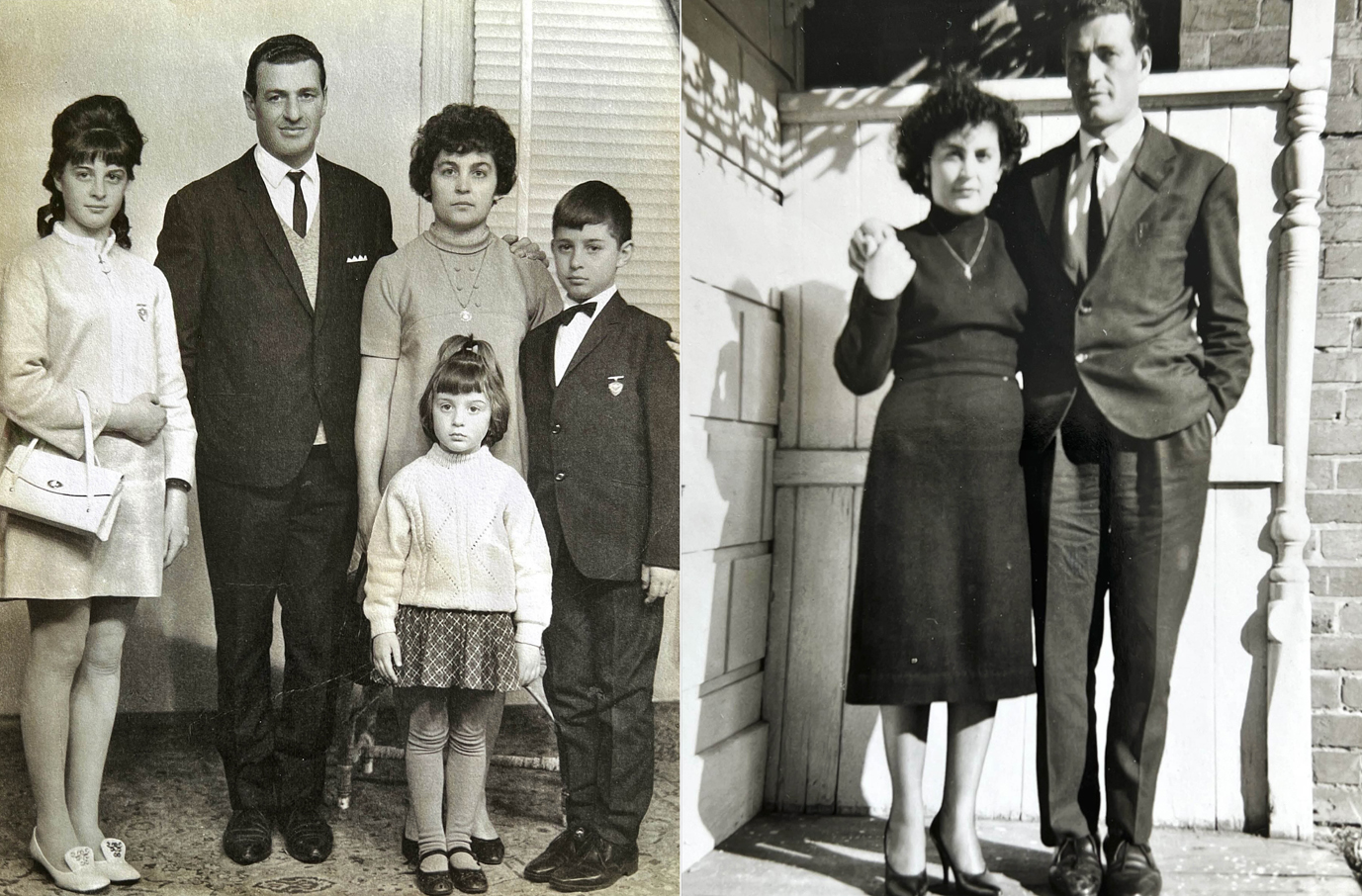

The couple were both from the province of Foggia: Michele from San Severo and Pasqualina from Castelnuovo della Duania, though they had a proxy wedding.

“The families obviously knew one another, but my father had already migrated to Melbourne,” Tartaglione said.

“In their wedding photos, my mother is always next to her brother-in-law.”

Tartaglione first attempted to piece together her family tree in 2003, but was soon thwarted.

Four years ago, she recommenced her efforts, prompted by a sign outside CO.AS.IT.’s Museo Italiano in Melbourne which read: “Do you want to find out more about your Italian family?”

“You need at least some information about your grandparents and their hometowns,” she explained.

“That gives you a starting point.

“I went to Italy for the first time in 1973, then again in 1985 when I met my grandparents, who were extraordinary people.

“I vividly remember my mother’s constant desire to leave Australia and return to Italy, but my father never wanted to.

“I returned to Europe with my husband and was there from 1988 to 1989, and I was last in Italy in 2011.

“When I’ve travelled to Italy, I’ve felt a connection to my distant relatives.

“I’ve always been ‘the Australian grandchild, niece or cousin’.

“I realised I was intrigued by my heritage and what makes me, me.”

Tartaglione used two platforms for her research: Antenati, an Italian website, and FamilySearch, a non-profit site run by thousands of global volunteers from the Church of Latter-Day Saints.

Every Tuesday and Saturday, she would travel to Wantirna to access the Family History Centre for four hours.

During this process, she connected with a distant relative residing in Bologna, Pasquale Antonino, whose great-grandmother, Giuseppina Tartaglione, shared her name.

“Nobody else in my family is interested in doing the research, which is why it was nice to find someone who shared my curiosity,” she said.

“As he lives in Italy, Antonino has the opportunity to visit San Severo twice a year and go through the ecclesiastical archives in person.

“We started exchanging information and with his help, I managed to trace the paternal branch of my family tree back to 1702.”

Though Tartaglione has faced numerous difficulties on her journey, from changing names to the evolving nature of the Italian language, indecipherable handwriting to Latin translations, she has not given up.

She dreams of living in Italy for a few years, perhaps in Santa Croce del Sannio, in the province of Benevento, where her mother lived before the family moved to Puglia.

She aspires to write a small book about her findings to share with her relatives and two daughters.

“I like to think that by finding out about my ancestors, I am closer to them,” she said.

“I hope I can do them justice, recognising their sacrifices and remembering them.

“I’m a product of my predecessors and I’ll always be grateful for this.”

If anyone is interested in reconstructing their own family tree, Tartaglione is available to offer advice and suggestions via email.