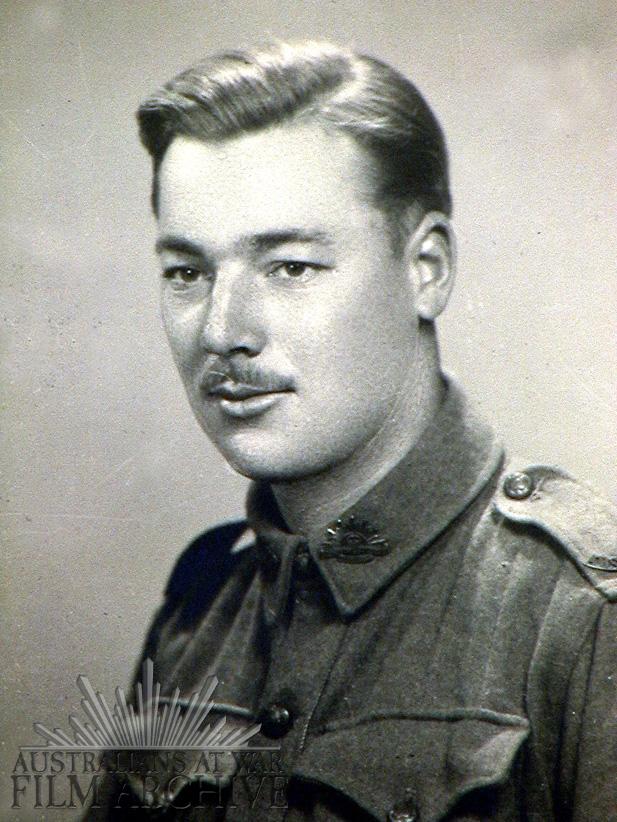

Bill Rudd OAM has been all of the above and his life a series of adventures, twists and prestigious awards for his contribution to historical memory.

On Saturday, December 9, 2017, the veteran soldier celebrated his 100th birthday at the MCG, surrounded by friends, family and authoritative figures.

It was an important milestone which doesn’t mark the end of an era, but rather celebrates a commitment which continues to this day.

Born in Essendon on December 7, 1917, Mr Rudd was stationed in El Alamein, in Egypt, in July 1942.

It was during the famous first Battle of Alamein, between the British army and the Italian and German forces.

His duty was to clear mines late into the night to allow the advancement of allied troops and tanks.

It was there that he was captured, alongside many other Australian, New Zealand and English troops, and detained in the POW camp at Bengasi, in Libya.

On August 17, 1942, Mr Rudd found himself among some 3200 prisoners aboard the Italian cargo ship Nino Bixio, destined for Italy, when the ship was torpedoed by a British submarine off the coast of Crete.

The ship didn’t sink, and was escorted to the Greek city of Pylos, where around 200 soldiers killed in the attack were buried and the surviving soldiers imprisoned.

Mr Rudd recalls with affection the kindness of the people of Pylos, who risked severe punishment to bring the prisoners figs and tomatoes to eat.

The survivors were eventually shipped to Bari and, from there, sent to the various Italian POW camps.

After a long train ride from the “heel of the Boot”, Mr Rudd arrived at Camp 57 in Grupignano/San Mauro, near Udine, a camp sadly renowned for its brutality.

“A hellhole,” as Mr Rudd remembers it.

There, he met another prisoner of war from Melbourne, Gordon Dare.

Mr Dare was captured in 1941 in Derna, Libya, and he nursed Mr Rudd through successive attacks of amoebic dysentery, influenza and jaundice soon after his arrival.

The two soon became inseparable.

Like some other 800 Anzac soldiers, they spent some time in Camp 106 in Vercelli, where they were sent to work in the area’s rice fields.

In the confusion following the armistice of September 8, 1943, Mr Rudd was helped by local farmers to acquire civilian clothing and escape on foot to Switzerland, using the few Italian words he knew to trade cigarettes for boiled potatoes.

“I had my liberty wrenched from me. I wrenched it back,” he told the ABC in an interview.

Mr Rudd remained in Switzerland for 15 months, and it was there that he met a Dutch girl who would soon become his wife.

Their marriage lasted 69 years and was accompanied by the birth of four children.

Mr Rudd’s friendship with Mr Dare had a lasting impact on his life.

Mr Dare passed way from a heart attack aged 56, and his wife asked Mr Rudd to recount to her their time in Italy, “of which they had never spoken”.

This sparked the beginning of a lifelong research mission.

Mr Rudd admits that his generation don’t like to speak of the war and the painful experiences which many veterans bottle up forever, not even sharing them with their family or close friends.

“I put the war behind me. I’ve always looked to the future,” he said.

But the request of Mr Dare’s wife, Joan, reopened a door to the past that led him to undertake extensive research into the Australian army’s archives to revive the stories of around 2000 Australian POWs in Italy during World War II.

“The Australian records weren’t complete,” Mr Rudd explained.

“They also weren’t correct.”

Therefore, his mission was - and still is - to clarify the facts.

Examining army records, Mr Rudd has managed to compile a list of 419 Australian POWs who arrived in Switzerland in civilian clothing and unarmed.

This list is now available at the Australian War Memorial’s Research Centre, in the Canberra RSL’s central library and in the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern.

But the huge research project to make sure that the stories of POWs aren’t forgotten is much more extensive and is compiled by Mr Rudd himself and available on his website.

Three years ago, Mr Rudd returned to Udine - accompanied by the Australian Ambassador to Italy, Mike Rann - to attend the inauguration of a marble plaque in memory of the Anzac soldiers inside the “Chiesetta” (church) of Camp 59.

The building was constructed by the very same Australian soldiers, using material supplied by the Vatican, and was restored after being destroyed by a lightning bolt.

Its reconstruction was funded by Australian and New Zealand veterans, among them Mr Rudd.

Last December, Mr Rudd received a letter from the National Association of Engineers and Transmitters (ANGET) in Premariacco, near Udine - of which he is a “free citizen” - congratulating him on his 100th birthday.

It is just one of the many demonstrations of affection and gratitude he has received for his tireless work.

At his birthday celebrations, everybody had the chance to share their story with Mr Rudd, each a fragment of an incredible mosaic reflecting an incredible century of life.