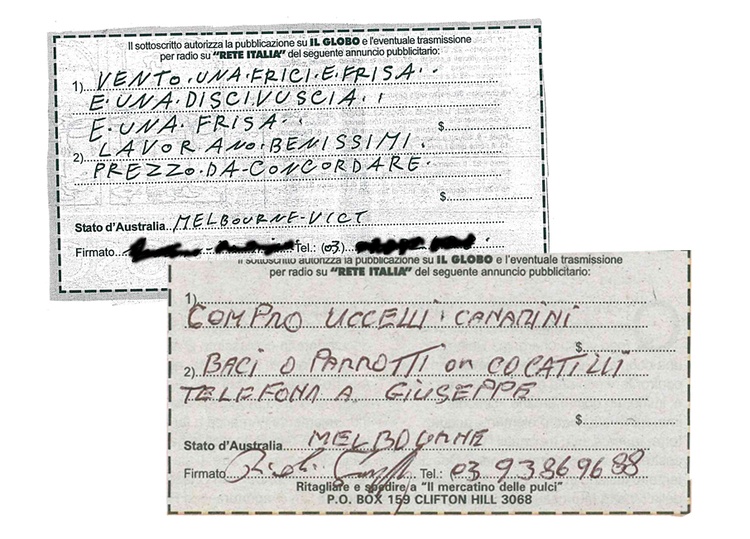

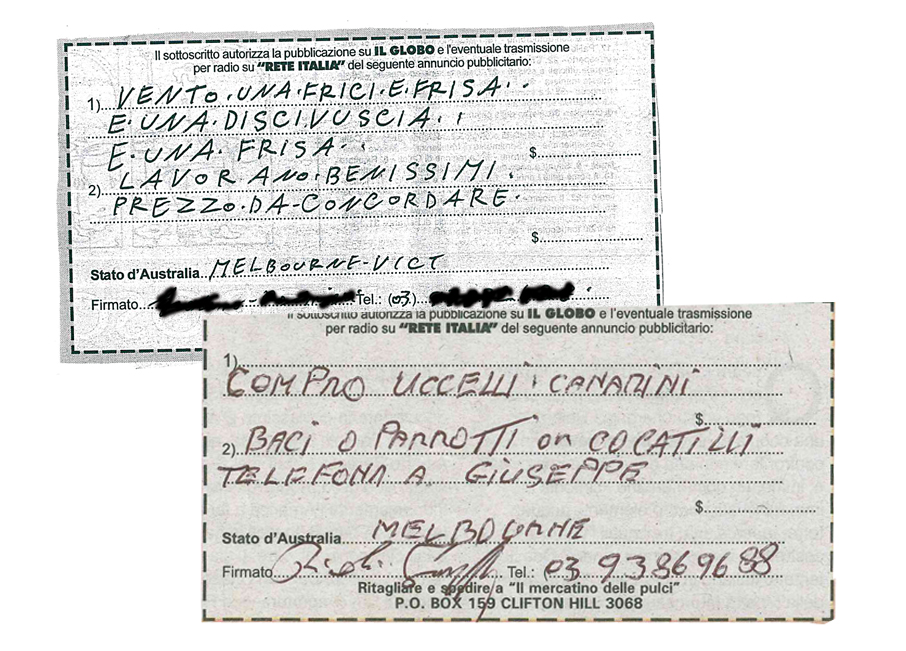

No uorris, you have every right to be: these words belong to a real language complete with its own dictionary and studies.

The fusion of Italian and English in Australia has led to the creation of a unique lingo which is used in certain contexts within the Italian community Down Under.

We spoke about this peculiar language a few years ago with Laura Zorzi, a young Italian who wrote a thesis on the phenomenon of “Australitaliano”.

Before her, other experts had analysed the language, which was born “during the first migrant wave between post-World War II and the 1970s, out of dialects, common Italian and the unknown Aussie English”.

“Loved and hated by scholars such as Leoni, Comin and Andreoni – to name a few – it’s an indispensible tool for communication for many who immigrated during the ‘50s and ‘60s,” Zorzi wrote.

“Despite strong incentives to promote the preservation of Italian, there was an omnipresent propensity to shiftare (the perfect example of Australitaliano!) to English, dictated by the need and willingness to integrate into the new English-speaking environment.

“A scrambled language like Australitaliano is therefore an unconscious compromise to communicate in a foreign land without completely abandoning one’s origins ... and it’s bladi cleva!”

But how does it work?

“Italian takes on terms or meanings in English, whether they are simple nouns or verbs, adverbs or adjectives, which are then adapted to Italian speech patterns and grammatical usage,” Zorzi explained.

“For example, the plural for the word concrit (concrete) is concriti, while muvi (movie) stays the same because the ‘i’ on the end already indicates the plural (even though in some cases the ‘s’ from the English is used for the plural).

“On the other hand, most verbs almost automatically take on the infinitive ending in ‘are’, for example ‘to bet’ becomes bettare.

“Meanwhile, adverbs and local expressions are faithful to their English origins, for example ‘alright’ becomes orrait.”

Other examples include: chemista (chemist); fenza (fence); checca (cake); grosseria (grocery store); deliverare (to deliver); smesciare (to smash); and moppare (to mop).

There are also some “false friends” to look out for...

In Australitaliano, fattoria means “factory”, while in standard Italian it exists as “farm”.

Instead, “farm” becomes farma.

Other examples include: petrolio (petrol, not oil); and applicazione (application e.g. job application, not phone app or to apply makeup).

While new arrivals in Australia have a better knowledge of English than their precursors, some of these terms are still used today and more are continually being coined!

For example, someone from Il Globo recently let slip the need to ciargiare their phone...

Do you have any Australitaliano words to share? Let’s hear them!