It seems strange today to think that they walked through these very same arid fields, strolling among their first wooden dwellings and observing, high up on the wall, that ever-repulsive weekly menu.

Retracing the history of the Bonegilla migration camp means inevitably subjecting oneself to the most diverse range of human emotions ― terror, fear, unease and calm.

Those who lived in that remote reception centre often speak of isolation and broken promises, but they also remember the warmth of the community, and friendships that often survived the passage of time.

Leaving behind razed cities and separated families, over 320,000 migrants from over thirty nations reached that former military camp in the heart of the Australian bush between 1947 and 1971. There were as many as 21,251 Italians, the fourth largest number of arrivals after those from Germany, Yugoslavia and Poland.

The first arrivals were dubbed ‘displaced persons’, or evacuees, escaping the horrors of the Second World War; only later, in the late 1950s, did thousands arrive simply because they were attracted by the advertisements of embassies across the European continent.

“At the time, Canada was competing with Australia in the search for new citizens, which is why the slogan ‘Come to sunny Australia where it’s always warm’ began to be used,” a guide at the Bonegilla Migrant Experience recounts.

“So a lot of people arrived without winter clothes and then had to wear all the clothes in their suitcases to survive the freezing nights.”

According to Giuliana Postregna, whose father Agostino has been honoured with a commemorative plaque on The Arc Memorial Sculpture in Bonegilla,

“It felt so cold in the winter months that he was forced to sleep under his mattress so as not to freeze, directly on the iron planks made from old gates of local farms.”

New arrivals were always assigned a bed, and towels and blankets were provided. Men and women, however, stayed in separate huts, and families were very often separated. No government official ever explained the reason for this division nor explored the emotional impact this rule might have had on the migrants. It was not until 1951 that the huts were divided into closet-sized cubicles, each just under four metres by three metres, in order to accommodate entire families.

However, it was always the government’s intention for Bonegilla to serve as a starting point for migrants to catch their breath before joining the Australian community; the camp was “wholly unsuitable for long-term family life.”

Staying at the camp meant, however, that the migrants had ‘guaranteed work’, even if this was enforced by the Australian authorities: “They could only refuse once; at the second proposal they had to accept.”

Around one thousand migrants were employed directly in the centre in a variety of occupations: from the kitchen to the garden, from the hospital to transport services. The conditions of public service guaranteed greater security, more reasonable wages, prospective overtime and promotions. Not everyone, however, gave the migration camp a chance; indeed, many left the area shortly after arrival on Australian soil for the capital of Victoria.

Patrizia Iovino arrived in Bonegilla with her family in June 1959: her parents Bruno and Luisa, and her sister Roberta, who was only four months old. She remembers those distant days perfectly, “in that immense space, in that endless countryside.”

The Pavan family at the port of Trieste on their way to Australia. (Photo provided)

“We were only in the camp for a month. I was seven years old, and I have never forgotten the taste of that disgusting food,” says Iovino.

“Milk was scarce. There was always boiled mutton and square white bread like cardboard. My mother took the train to Albury every week to buy something edible for us.”

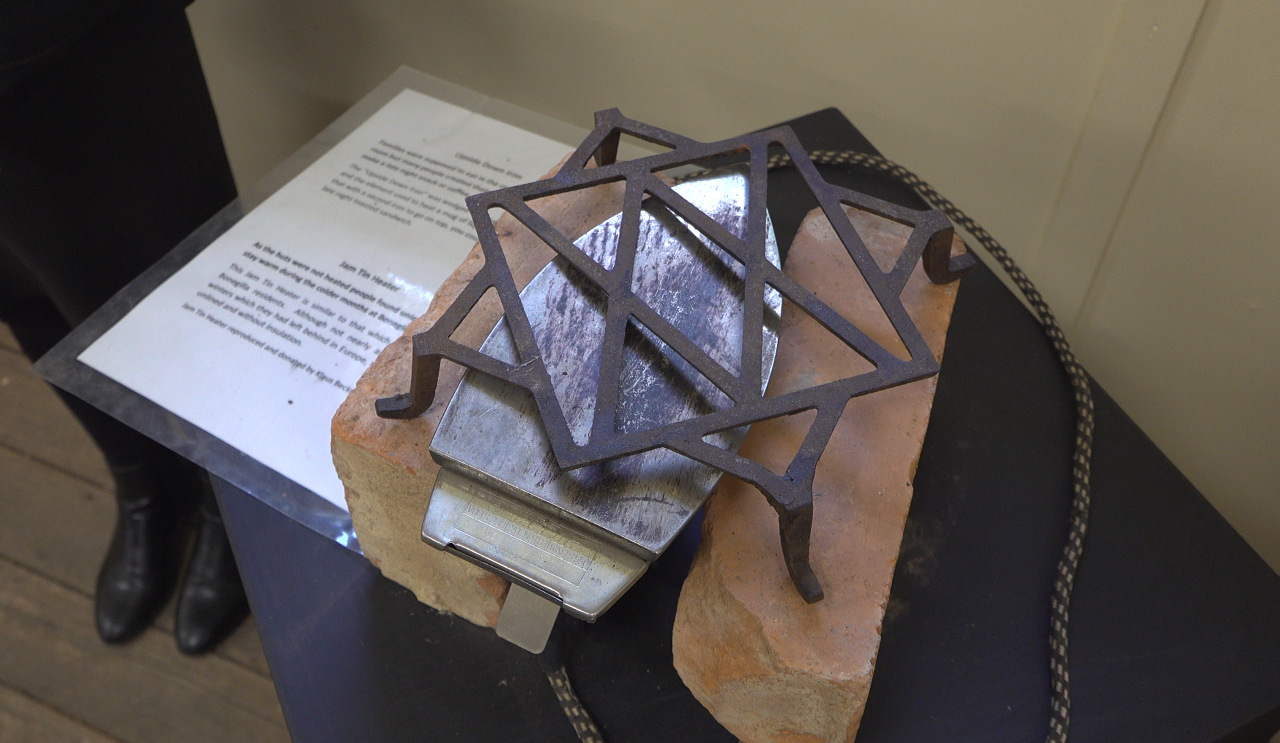

In fact, many tried to avoid the questionable food served in the communal canteens, conspiring to use gas cookers hidden between rows of laundry, or using an upturned iron placed between two bricks, in order to cook in their rooms.

The stove designed by migrants to be able to cook secretly in their rooms (Photo: Albury Library Museum)

It was during the economic recessions of 1952 and 1961 that large numbers of migrants took part in frustrated demonstrations: they had left their jobs in their homeland for the promise of ‘a better life’ and, faced with this reality, felt cheated. These feelings of dissatisfaction provoked several riots, which were suppressed by the army in 1952 and by the police in 1961.

Both expressions of discontent received national and even international attention. Il Globo followed the story, with a special correspondent at the camp, and the publication of an in-depth report on its front page on July 25, 1961.

“My father kept waiting for a job that wasn’t coming, so he decided to take a train to Melbourne, with an Italian friend he had met at the camp,” Iovino recounts.

“He immediately found work as a turner, the profession that had allowed him to reach Australia as a skilled worker. We left the destabilising experience of Bonegilla behind us.”

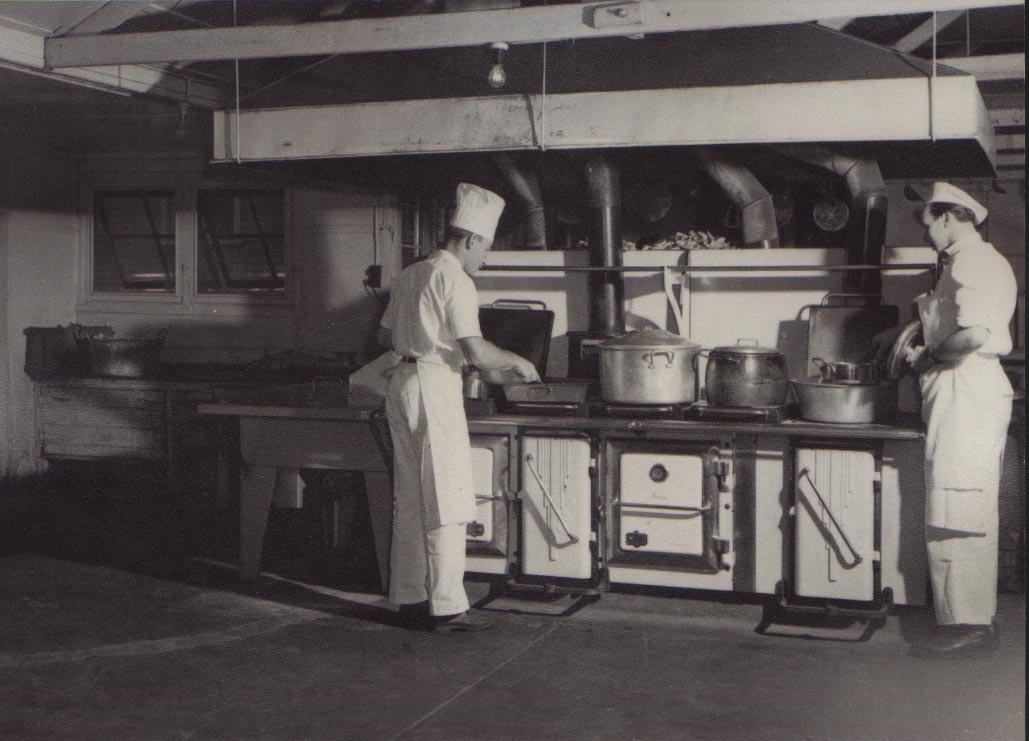

The kitchen at the Bonegilla camp. (Photo: Albury Library Museum)

The reception centre is still a place of pilgrimage, and celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, a milestone commemorated with a week full of activities: the opening of an exhibition on the migrants’ historical documents, ‘ID Experience’, a bus tour of the camp’s extensive grounds, and a screening of Bonegilla Stories, a series of short films retracing the accounts of former camp residents, conceived and realised by Simon Reich.

Despite the inexorable passage of time, many still remember their mothers crying about the “cultural trauma”, the embarrassment of hearing strangers speak to their parents “as if they were simpletons”, simply because they were not used to communicating in English. Many felt the humiliation of being forced to clean the camp’s toilets and kitchens.

Australia actually welcomed the newcomers as a ‘controllable labour pool’, crucial to the country’s post-war reconstruction. But migration has gone down in history as a bittersweet experience: for some, it’s a starting point; for many others, an experience of loss and displacement.

Whether it was a short or long stay, Bonegilla irrevocably marked a significant stage in the lives of so many - a transition zone between an irreparable past and a future suspended in a haze of hope.