And this is despite a stroke that the 76-year-old, who was born in Trieste, suffered two and a half years ago.

“Even my specialist was very surprised that it didn’t affect my speech,” he said.

Evidently, Magris is still agile and able to avoid the blows inflicted by life, as he once dodged his opponents’ blows in the ring.

On the other hand, his passion for the sport has always extended far beyond the pure adrenaline of competing.

In his home in Sunbury, around 40 kilometres north-west of Melbourne, Magris has a room full of books, magazines and memorabilia related to boxing.

In 2004, he became the first Italo-Australian to be inducted into the Victorian Boxing Hall of Fame.

He’s also the longest-serving secretary of the longest-running boxing association, the Past and Present Boxers Association, founded in 1938; he’s proudly held the role for 25 years.

Magris inherited his passion for boxing from his father, who would tell him stories about the sport from a young age.

“My father was at the fight when Primo Carnera defended his heavyweight title in Rome,” he said.

Magris migrated to Australia in 1954, at the age of 10.

Upon their arrival in their new home, his father took him to the West Melbourne Stadium (later renamed Festival Hall) to cheer for Italian champions such as Bruno Visintin, Duilio Loi and Mario D’Agata (who was the first, and so far only, deaf boxer to win a world title).

“In those days it was hard for Italian immigrants,” Magris said.

“They were still called names and discriminated against.

“When the Italians came and fought the Aussies it was really something; they used to fill the stadium up.

“I was there the night of the riot during the match between Bruno Visintin and African boxer Attu Clottey, in 1957.

“Visintin won the fight but he never got the decision; the referee gave Clottey the win.

“The Italians went crazy and threw bottles; one of the bottles missed me by inches.

“I was just a kid and I had never seen anything like it.

“From that day on, they stopped selling glass bottles at the stadium!”

Magris began training at the age of 13 and reached the peak of his career in the 1960s, fighting in the bantamweight category.

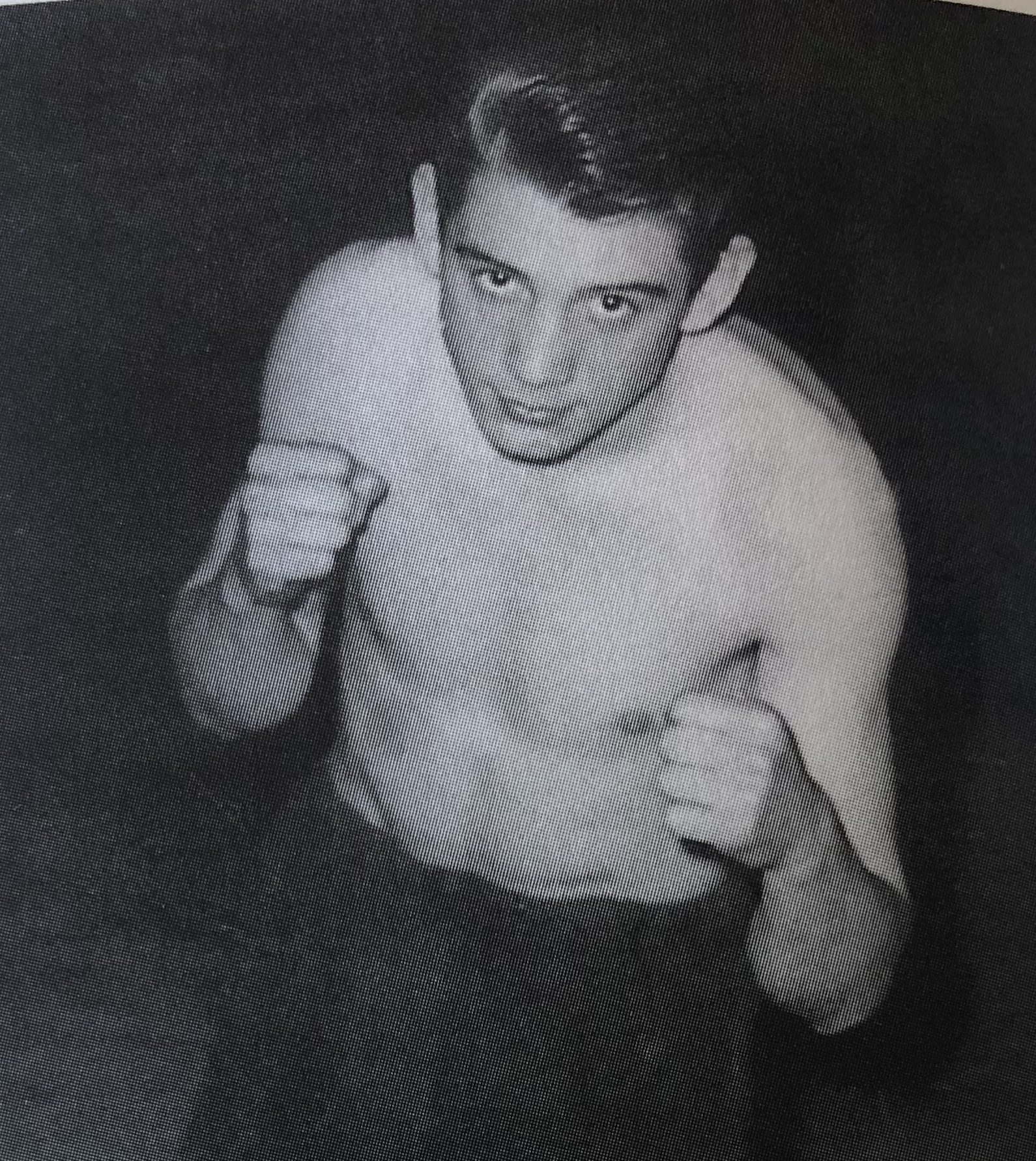

An image of Mario Magris at the age of 21

Over 12 years, he fought in 78 matches, 31 as a professional.

“I was described as a fast and skilful boxer,” he said.

“I had a few minor injuries but in all the fights I had, I never got cut.”

Magris was at the height of his career when a blood disorder forced him to give up boxing.

“It was a rare form of chronic anemia,” he explained.

“I tried to make a comeback after a few years but it wasn’t very successful.”

Magris is best known for his three fights with Lionel Rose, the first Aboriginal boxer to win a world title and also the first Indigenous person to be named Australian of the Year.

“I’ve won a lot of fights but most people remember me for my three losses against Lionel Rose,” he laughed.

“I was able to take him to three very close decisions each time.”

Magris’ forced retirement from professional boxing did not affect his passion for the sport, and he continued on as a trainer and as a member and then secretary of the Past and Present Boxers Association.

“We meet three times a year at the Darebin RSL and remember the good old days,” he concluded.

“We have around 200 members and we also had several women on the committee, which not many boxing clubs do.

“Boxing has given me a lot of satisfaction and honours, but above all, I value wonderful friendships that have lasted over the years.”