It’s a story of treatment, hospitality and integration.

It’s also a story of a time in which faith and secularism united in their love of helping those in need.

It’s a story of multiculturalism, with many characters dedicated to understanding beyond geographical and social barriers.

A story perhaps already known, but not well enough.

On January 24, 1948, ten Italian nuns were sent to Melbourne by the pope to assist Italian immigrants arriving in Australia after WW2.

The nuns’ missionaries were part of The Order of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, founded in 1880 by mother Francesca Saverio Cabrini in Lombardy.

Mother Cabrini’s desire to help Italian migrants began during her travels to the United States, where she had the difficult tasking of reading a letter to an illiterate patient regarding the death of their mother.

Cabrini became convinced of the need to open special facilities for Italians living abroad who had difficulty communicating.

It was this vision that guided the mission of the ten nuns in Melbourne who were asked to take care of St Benedict's Hospital in Malvern, which at the time was in disrepair.

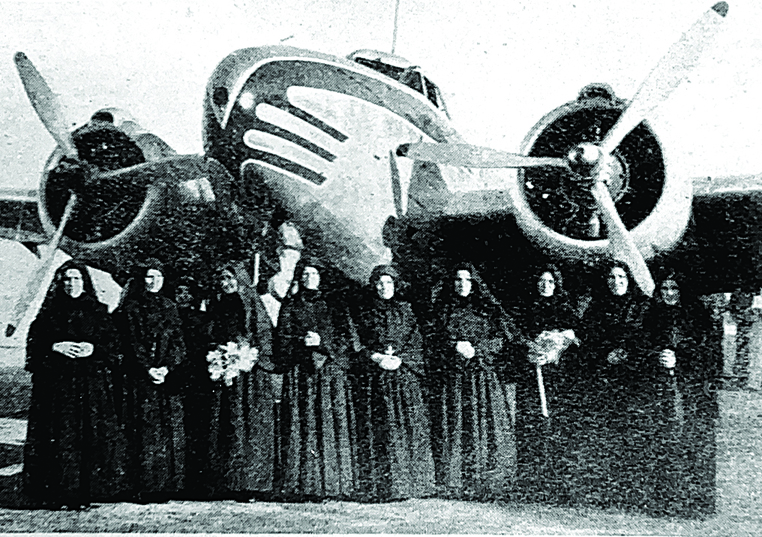

For them, the journey to Australia was a nervy one, arriving on a “funny little plane”.

"Some of them didn't even have seat belts," recounted Julie Fleming, Cabrini Group Director of Mission and Identity.

"At the time, the sisters were kept separate from the few other people who were also on board, as they were all men.

“They had to stop at lunchtime for meals and to go to the toilet, it took them 12 days to get here.”

The arrival of the ten nuns in Melbourne after their lengthy journey from Italy

Initially, the sisters thought they could quickly convert the hospital into a functioning facility but, alas, upon arrival they found little more than an abandoned house.

The cleaning alone took them weeks.

The challenges did not end there; only three of the ten sisters spoke English, while only two were actually nurses – one was a nurse’s assistant, and one was a radiologist.

The other six only had experience with cleaning and cooking.

"The Italian community are totally responsible for the success of the Cabrini sisters in Melbourne," Fleming declared.

"They were so thrilled that the very first Italian order of nuns had come to Melbourne.”

“Although there was at times prejudice towards Italians after their collaboration with Germany during World War II, the religious community always had the respect of locals, especially those in Malvern."

Fleming fondly recounts how members of the Italian community would leave the nuns food and milk as gifts on the landing of the hospital building.

An Italian community group visiting Coonil House, site of the then original St Benedict's Hospital, in 1949

Life at the hospital literally depended on teamwork.

One example of this comes in the form of a young man with appendicitis who needed help getting up and down the stairs of the hospital.

The doctors, along with an Italian driver and even the gardener, all helped carry him.

But the conditions under which the sisters operated daily were so difficult that when their Mother Superior visited from Italy, she immediately saw that changes were needed.

She proposed the construction of another hospital building which was inaugurated in May 1958 by Archbishop Mannix of Melbourne.

That building is the very same that stands there today.

Over the years the hospital has expanded and evolved, helping it to be voted the second-best private hospital in Victoria in a Newsweek poll in 2023.

Many other successes, such as Victoria’s first ever open-heart surgery in 1985, was possible only because of continued support from Italian migrants.

For decades, special people like Lena Santospirito helped raise funds for the hospital through events involving the Italian community, and especially Italian women.

There are still many contributions from Italians today, which are crucial to the hospital's growth and organisation.

The Cabrini Hospital today. (Photo: Peter Clarke)

"It is absolutely and utterly because of the Italian community that Cabrini exists today," Fleming revealed.

“What was so interesting, I found, was that the sisters didn’t speak much English … but they were much loved for their comfort and care for patients.”

She recalled how one of them used to cook spaghetti and serve red wine to patients who, at first were puzzled, but later appreciated the hospitality.

“We have testimonials from patients at the time and [what they spoke of] was how loving they were," Julie concluded.

“It was very practical love, bedside love.”