The €750 billion ($1.2 trillion) deal will provide a vital lifeline to the Mediterranean countries hit hard by the pandemic.

It was sealed after more than 90 hours of intense negotiations that saw threats of a French walkout and a Hungarian veto – and fierce opposition from the Netherlands and Austria to too generous a package.

“These were of course, difficult negotiations in very difficult times for all Europeans,” EU Council Chief Charles Michel, whose job was to guide the tortuous talks, said.

He dubbed the summit “a marathon which ended in success for all 27 member states, but especially for the people”.

The package was made possible by the crucial backing of Germany and France and includes the biggest ever joint borrowing by the 27 members of the bloc, something that had been resisted by Berlin and the so-called “frugal” northern states for generations.

Italy will receive the largest share of the package, €209 billion or 28 per cent of the total, with Spain receiving the second-largest.

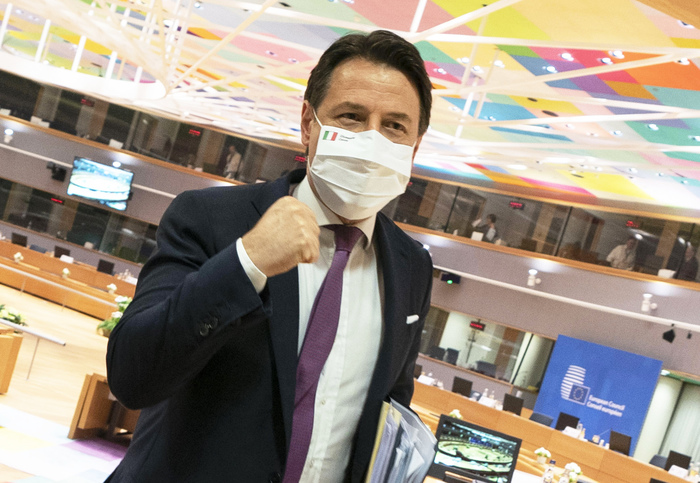

“It’s a historic day for Italy,” Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said.

“We have a chance to relaunch Italy with strength, to change the face of our country.”

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte. (Photo: ANSA)

He said Italy would receive even more than had been earmarked in earlier proposals.

That money will come in the form of loans and grants – the grants being more important for southern European countries, which are already struggling with high levels of debt.

In April, the bloc’s finance ministers approved a smaller stimulus package, but Italy and other countries walked away, saying a broader effort – involving the joint issuing of debt – was still needed.

When debate about the pandemic response kicked off, many southern Europeans were fearful that any ambitious plan might unravel amid rancor – in a replay of the divisions among EU nations over sharing the duties of accepting asylum seekers during the height of the migration crisis.

In Italy, in March and April, even reliably pro-European politicians warned that the future of the bloc was at risk.

France and Germany were initially reluctant to share medical equipment, and Italy’s proposal for “corona bonds” was shot down.

Nathalie Tocci, director of the Italian International Affairs Institute, said on Tuesday that the tune in Rome toward Europe has “changed fairly dramatically” since then.

She said this European deal would prove to be the enduring memory.

“The EU had been doing the bare minimum to survive, and this time it didn’t,” she said.

“All of the divisions that we’re so used to talking about, notwithstanding all of that, we did it.”

The Euroskeptic, far-right League party remains Italy’s most popular, and its leader, Matteo Salvini, criticised the rescue package as a “big rip-off” in which Rome would be subservient to Brussels.

But both the League and Salvini personally have bled support during the pandemic, while the centrist Conte has risen in popularity.

Matteo Renzi, a former Italian prime minister and a member of Conte’s governing coalition, said the deal was an “excellent result” for Italy and a “masterpiece” for Europe.

“The sovereigntists lose,” Renzi wrote on Twitter.

“The agreement shows that a pro-European government is good for Italy.”

The recovery package will complement the unprecedented monetary stimulus at the European Central Bank, that has largely succeeded in reassuring the financial markets despite a catastrophic recession in Europe.

The rescue package was agreed along with the EU’s long-term budget, bringing the agreed spending to €1.8 trillion through 2027.

The package now requires more technical negotiations among member states as well as a ratification by the European Parliament that could happen as soon as Thursday.