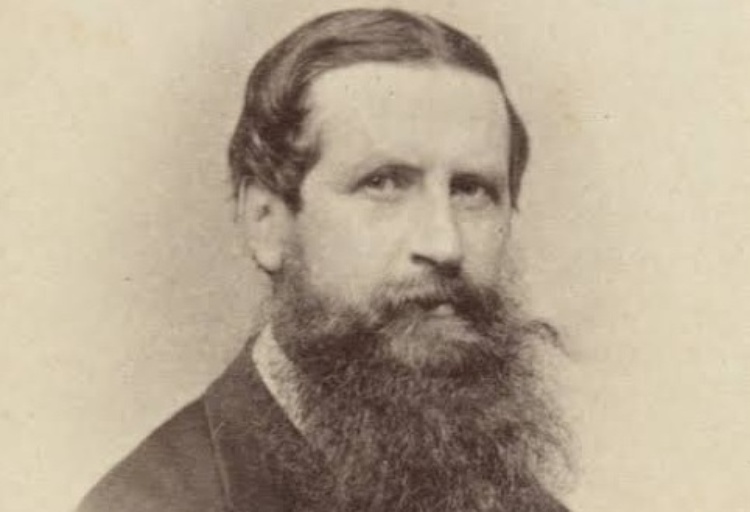

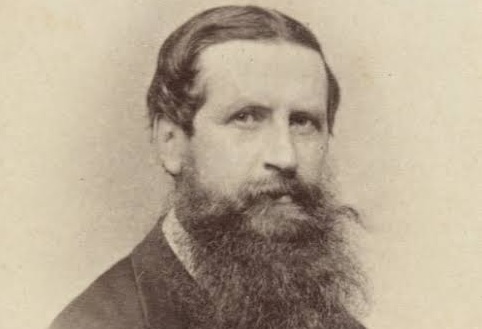

Tuesday, December 3 marks the 165th anniversary of the Eureka Stockade, and it was an Italian immigrant, Carboni, who produced the only complete eyewitness account of the rebellion of 1854.

Carboni fought with the armies of Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, to liberate Italy against the ruling Austro-Hungarian Empire.

He later fled the collapse of the Roman Republic and made his way to the Victorian Goldfields.

Associate professor Gaetano Rando of the University of Wollongong has researched and written at length about Carboni.

Most notably, Prof. Rando has published a book about Carboni’s Eureka crusade including the only Italian interpretation of Carboni’s manuscript, something that Carboni never got around to writing himself, entitled La barricata dell’Eureka: Una sommossa democratica in Australia.

Prof. Rando’s book is especially significant as it contains several chapters covering Carboni and the Eureka Crusade, and a section featuring a collection of letters that Carboni wrote when he returned to Italy, which related to his participation in the Italian Unification, or Risorgimento.

Prof. Rando describes Carboni as someone who had a “leading role in the Eureka Stockade”, which was a rebellion by gold miners in Ballarat against government troops.

Thirty-five people died in the skirmish, which was fought over licensing fees that were deemed to be unfair by the prospectors, who also opposed the heavy-handed tactics by government officials and the manner in which these fees were extracted.

Conversely, the government troopers – many of whom were ex convicts – couldn’t keep order in the goldfields.

“The confrontation on the goldfield progressively escalated [until] the government in Melbourne sent an army detachment [with] the intention to crack down on what was happening on the goldfields,” Prof. Rando explains.

Carboni wrote that “the diggers, outraged at the unaccountable conduct of the Camp officials in such a wicked license-hunt at the point of the bayonet...rushed to their tents for arms and crowded on Bakery-hill”.

“They wanted a leader ... No one came forward.”

Carboni credits himself with creating order and organising the rebels.

He also talks about the barricade and how bad it was compared to in Europe: “In the 1848 uprising of Rome there were leaflets floating around on how to build a barricade.”

After the miners had armed themselves and were positioned behind the barricade they had erected, a spy reported their movements to the military, which decided that it would be a good time to crack down and that the attack would take place at dawn.

Carboni was absolutely exhausted from the night before and had gone to sleep in his tent only to be woken by the sound of musket fire.

It is this detailed and personal account which is the only known complete first-person record of the Eureka Stockade, published a year after the event.

Carboni was arrested for treason but was later acquitted.

Using the gold that he had mined for, he travelled to the Northern Hemisphere and eventually returned to Italy, where he participated in the Expedition of the Thousand, an event of the Risorgimento.

Aside from his significant writings on the Eureka Rebellion, Carboni also wrote several theatrical pieces.

In the early 1980s, the Municipality of Urbino erected a plaque on the house which was thought to be his home.

“His hometown actually got around to staging one of his plays, which is probably one of the only times that his work was actually performed,” Prof. Rando says.

Prof. Rando underscores Carboni’s work by suggesting that the revolutionary is “the Italian writer who has made the most impact on Australian literature, although a controversial one”.

“We certainly need to remember [Carboni] for his contribution in the Eureka Stockade and for writing the only eyewitness account,” he adds.

Here is a man who helped shape the Republic of Italy and Australia; it is our role as Italo-Australians to honour his legacy.