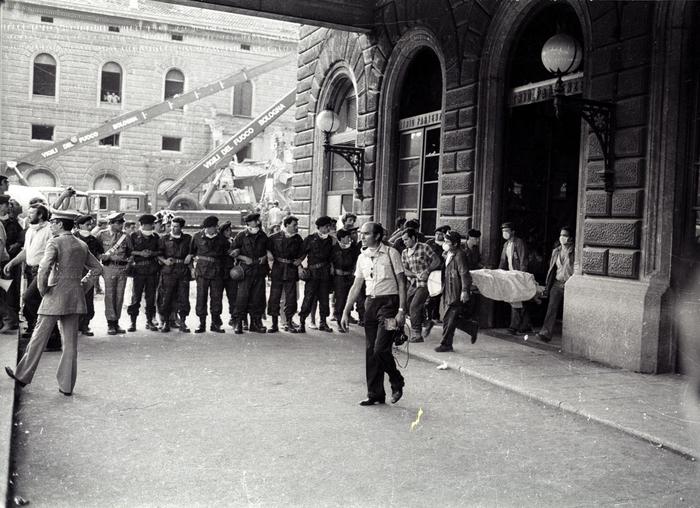

On August 2, 1980, a powerful explosion ripped apart the waiting room of Bologna’s central railway station, leaving 76 people dead and 200 injured in a terrorist attack that shocked the nation.

Some of those injured later died, bringing the total death toll to 85.

A device left inside a suitcase in the second-class waiting room at Bologna’s train station exploded at 10:25 am.

It was a hot summer weekend and that waiting room, unusual in having air conditioning, was full of people escaping the heat.

The room where the device was planted was destroyed, as was an adjoining restaurant.

The victims were a mix of station staff, local Italians and tourists, including several foreigners.

The youngest was a three-year-old girl, named Angela Fresu.

The northern Italian city plunged into chaos following the attack: it was unprepared for such a devastating event, and did not have enough ambulances to transport the wounded.

Some were taken to hospital in taxis.

Photo: ANSA

At first, those present thought the blast was an accident; a gas explosion perhaps.

It wasn’t until later in the morning that police began to investigate it as a deliberate attack.

Around midday, different terrorist groups began making claims of responsibility for the act.

The bombing remains Western Europe’s fourth deadliest post-war terrorist attack, and one of the most devastating in Italy’s history.

Photo: ANSA

It took place at a time of political turmoil in Italy and wider Europe.

It came as part of the so-called “Years of Lead” in the 1970s and early 1980s, during which the mafia, the far-left Red Brigades and neo-fascist groups carried out violent attacks all over the country.

After years of investigations, trials and false leads, Francesca Mambro and Giuseppe Fioravanti, members of the right-wing terrorist organisation Armed Revolutionary Nuclei (NAR), were sentenced to life in prison in November 1995.

Both, however, have always maintained their innocence.

Many others were also put on trial, some of whom eventually received prison sentences for supporting the terrorists or for obstruction of justice.

Among them were Licio Gelli, head of the infamous Propaganda Due lodge, and Pietro Musumeci, an officer in the Italian military secret service.

The trial lasted decades, with appeals, acquittals and multiple diversions.

However, it’s thought likely that some of those involved in planning the attack will never be brought to justice.

Photo: ANSA

In the city today, efforts are continuing to unearth new leads in the investigation.

On the 39th anniversary, Italian ministers proposed opening an 18-month “technical and non-political” enquiry aimed at “finding the truth” about the massacre.

As recently as January 2020, Gilberto Cavallini, a 67-year-old former NAR member, was convicted of providing logistical support for the bombing and sentenced to life in prison.

Suspects are still being sentenced to this day, suggesting the case isn’t fully closed.

The ongoing sentencing seems to confirm the widespread belief that we still do not know the whole story and that Italy has struggled to come to terms with this horrible act of terrorism.

This state of seeming paralysis is symbolised by the fact that the main station’s clock has not been replaced and, as a reminder for future generations, still shows the exact time of the attack.

Forty years later, President Sergio Mattarella honoured the victims of the massacre and their families, reiterating the need for full truth and justice.

Mattarella laid a wreath at the commemorative plaque at the station during a ceremony with relatives of the victims, and attended a special mass at Bologna’s St Peter’s Cathedral.

“After paying tribute to the plaque that recalls the victims of the barbarism of the bombers, there are few words one can say: pain, memory and truth,” the president said.