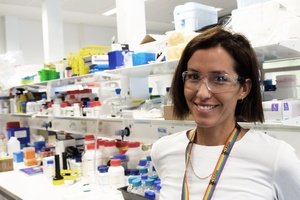

For 21 years, she has been the executive director of the Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health (MCWH), a community-based, not-for-profit organisation which increases migrant and refugee women’s opportunities for health and wellbeing in Australia through education, advocacy and leadership.

The organisation is led by and for women from migrant and refugee backgrounds, just like Murdolo.

After an initial stint living with family in Reservoir, Murdolo’s family moved to Moorabbin when her father, Vittorio, secured a job at the Philip Morris cigarette factory in nearby Cheltenham, where he went on to work for 30 years.

“My mother [Santina] didn’t speak English and she didn’t have all the modern technology; when they moved to Moorabin, they didn’t have a washing machine and my mum spent a lot of time washing nappies in the sink,” Murdolo says.

“She’d spend all her time in front of the laundry window, looking out while she was washing them, and the woman who lived in the next house thought she spent the whole day spying on her!

“But eventually they became really close friends; she was Anglo-Australian and she helped mum any time she needed to fill out forms or make phone calls in English.

“She’d come over every single day and have a cup of coffee and they’d chat; even though mum didn’t have a lot of English, they’d find a way to communicate.

“But at the same time, my mum started developing depression because she was quite isolated at home.

“She really wanted to get a job, because she knew that she needed to get out and mix with other people.

“In Italy, she was a very talented dressmaker but here she didn’t have the resources she needed to set up her own business.

“Her first job was sewing electric blankets and then she got other jobs, all in factories; it really helped her mental health and it was a lifesaver for her.”

Murdolo was raised on the rhythm of factory shift work.

Her mother would start work at 5:00 pm, allowing her to welcome the children back from school and have dinner ready to be heated up; then she would come home at midnight and clean up the house before going to bed.

Meanwhile, her father worked from 5:00 am until 1:00 pm, leaving the couple with only a few hours of the day to spend together.

Both originally from Roccella Ionica, a coastal town in the southern Italian region of Calabria, Vittorio and Santina had known each other since childhood and knew they were in love even before they had exchanged a single word.

“They’d communicate through friends and family,” Murdolo says.

“If dad was planning to go to the movies, his cousin would tell my mum’s cousin and they’d work out that he’d go and sit behind her at the movies.

“Even though it wasn’t acceptable for them to speak at that time, they had an unspoken love.”

At the age of 18, Vittorio decided to follow his family to Australia; his father had already migrated here to work on the tobacco fields and was slowly joined by the rest of the family.

“The ship docked first in Fremantle and my father went to a cafe off the port,” Murdolo recounts.

“He noticed that there was a big sugar dispenser and he’d never seen anything like it before; he sat there and had spoonful after spoonful of sugar.

“He couldn’t believe this plentiful place that he’d come to.

“After he’d established himself, he wrote to my mum and asked her to marry him and she agreed; he went back home, they got married and about six months later, in 1960, they got on the ship to come to Australia.

“My mum was already pregnant and within a month after they arrived in Melbourne, my sister Mareta was born.

“Then, I was born in Moorabbin and my brother Vince and sister Rita came along after that.”

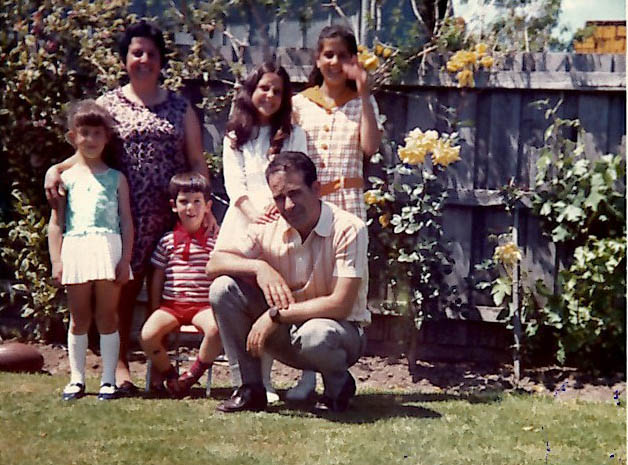

The Murdolo family in 1972 (left to right): Rita, Santina, Vince, Adele, Vittorio and Mareta

After studying Italian and women’s studies at La Trobe University – where she discovered the Italian feminist movement thanks to the enlightening lessons of Mirna Cicioni – Murdolo obtained a Masters and a PhD at the University of Melbourne, focusing on the history of the women’s movement in Australia and the migrant women involved.

“When I finished Year 12, I got a job in a bank and my mum advised me to apply for university,” she says.

“I worked at the bank for about six weeks and it drove me pretty crazy because it wasn’t very stimulating, so I ended up going to university; mum was quite instrumental in me making that decision.

“Our parents were really happy for us to make our own choices, but they highly valued education.

“My dad left school after Grade 3 and my mum after Grade 5; my dad was never academically inclined but my mum wanted to continue with her studies.

“They knew the difference and they encouraged us to not limit ourselves to the opportunities they’d had.”

Murdolo began working at the MCWH in 1994, when it was called Women in Industry and Community Health (WITCH).

This new beginning marked both a revelation and a rediscovery of a world she knew all too well.

“It was such an amazing feeling to know there was an organisation that acknowledged that migrant workers exist, because most of the time it’s invisible; people don’t think about where their food or clothes come from and that there’s a whole woman and family behind those products,” she says.

“I felt as though I’d found the right place for me as soon as I walked in.

“There were lots of other working class migrant women involved in the organisation, many of whom had worked in factories themselves.

“It was fantastic to be able to hold those three categories of identity and oppression – class, race and gender – together at the same time.

“That really spoke to me and excited me.”

In the 1990s, the Victorian manufacturing boom was already waning, with production moving offshore and the workforce in each factory shrinking.

Where once the MCWH would send employees from 12 different backgrounds to any factory to meet the same number of linguistic needs of the workers, by the ‘90s five were enough.

“There was also a shift to textile working from home so we were able to do some work with outworkers, which was much more difficult because everyone was isolated,” Murdolo says.

“Now, the largest sector is food manufacturing, as well as paper products.

“We also have migrant women working in different industries such as aged care, and we work with hotel staff, such as cleaners and women who prepare food.”

While some things change with time, certain needs and issues remain pressing.

For example, a lack of contraceptive information for migrant women in their language is still a major concern.

“We’ve just released a new report that shows migrant women still have lower access to sexual health and reproductive services and are less likely to use contraception,” Murdolo says.

“Only 60 per cent of migrant women use contraception, compared to around 70 per cent of women born in Australia.

“Especially in the ‘90s, ‘pre-Google’, it was very difficult to find information in different languages.

“We also dealt with sexual health, especially because at that time HIV became a big issue.

“In the early ‘90s, we ran a campaign on Depo-Provera, a form of contraception that’s injected and lasts three months.

“We found that migrant women were more likely to be given these long-acting contraceptives, without them really having the broad choice.

“Doctors wouldn’t have interpreters, so they weren’t able to communicate the range of options available to women and they’d offer something long-acting like an injection or implant.

“We wanted migrant women to be able to make an informed choice.”

Post-natal depression also remains an issue for migrant women, due to a lack of preventative action and social programs for migrant mothers.

Another concern is the struggle to receive treatment and compensation for occupational overuse syndrome caused by repetitive work.

“It’s an invisible injury because it’s not a one-off injury that you can see and quantify,” Murdolo says.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the disadvantages that migrant women experience.

“The virus itself has infected people from migrant communities more,” Murdolo says.

“More than 50 per cent of infections in the last Melbourne wave in 2020 were among people born overseas; this is an overrepresentation, because this group represents 30 per cent of the population in Victoria.

“I’ve also been told that more women are affected by the virus long-term than men and that’s something that I want to investigate more.

“Then there’s the economic effect; migrants are already earning less than the rest of the population and now they’re more likely to be affected by COVID-19.

“Another thing I’m trying to get more information on is vaccination data within migrant communities.

“I’ve heard anecdotally that there are a lot of challenges with accessing the booking system and people aren’t sure whether they have to pay for it; there are a lot of barriers so that’s my immediate concern.”

After almost 30 years at the MCWH, during which she has experienced and responded to continuous changes in the social fabric of an increasingly diverse Melbourne, Murdolo still finds her profession stimulating and rewarding.

Her passion for reaching migrant women is as strong as ever, and one of her long-term goals is to expand the organisation’s work to include locally-based resources in regional Victoria.

“At the moment we have staff who service rural areas, but they go to visit for a couple of days and then come back to Melbourne; we think it’s a much better resource for the local areas if they have trained bilingual educators who live in that same area,” Murdolo concludes.

“This year, we were able to set up a program like that with all of the local women’s health centres; we’d love to take that from a short-term project into a longer-term program that’s tailored to local communities.”