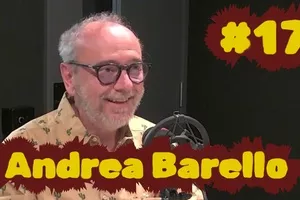

Greeting me in his clinic in Niddrie, he refrains from shaking my hand due to COVID-19 restrictions; under the blue mask, however, is a kind and hospitable smile.

The former president of the Australian Medical Association (AMA) speaks with fervour and says he is guided by a “mission”.

He has few regrets in life and would do it all again, perhaps with a slightly different approach.

“I’m a person who finds it difficult to say no to someone when they need help, so I took on more than I could possibly complete in the day,” he admits, speaking of the earlier years of his career.

“I was always working longer and longer, and finishing later and later.

“That’s my only regret – looking after people as opposed to being present for my family.”

I immediately get lost in Bartone’s life story; as a young child, he had already embarked on his mission of helping others, starting with his parents.

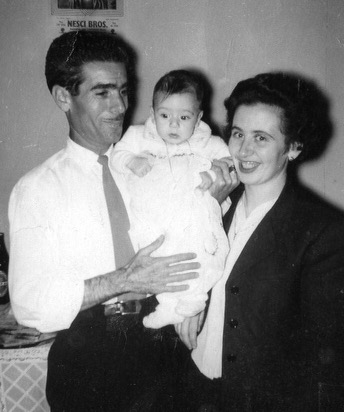

Hailing from the Calabrian town of Sorianello, his parents were “almost engaged” when his father left for Australia at the end of 1954; he was a 36-year-old war veteran in search of a better life.

The couple married by proxy, but fortunately, unlike thousands of other Italians, they already knew each other and were in love.

When the couple reunited in Melbourne, they first lived in Kensington.

A few years later, they realised every migrant’s dream – buying a house – and settled in Essendon.

“They had another son before me, but he was stillborn,” Bartone says.

“It was a time of great sorrow; they didn’t speak English, they didn’t know anyone in Melbourne, they were practically alone and the pregnancy was longer than expected – 42 weeks.

“Nobody knows what really happened, but it caused them great pain that I believe they felt right up until their last days in this world.

“They waited four years before trying to have another baby and then I was born.

“I often wonder what it would’ve been like to have had an older brother; I probably wouldn’t have been born or would’ve been born earlier... sliding doors, as they say.

“Whenever I brought that up, they both spoke affectionately and warmly about a human that never really took a breath.

“I know that it still hurt them in their dying days to talk about it.”

Bartone has a younger sister and two younger brothers, with a large age gap between them.

Growing up, he enjoyed school and was good at it.

“But I was different,” he says.

“My mum would come at lunchtime with hot pasta and everyone else was having sandwiches.

“I grew up with a lot of racism and I wasn’t very tall or athletic; the scholastic achievements came much later and then people started to take notice.”

As a young boy, Bartone helped his parents to overcome the language barrier that they faced in Australia, particularly when both of them suffered from health issues.

First his mother was ill and had to spend lots of time in the Outpatients clinic; then, his father was bedridden for a long time with sciatica.

A young Tony Bartone in his parents’ arms. (Photo supplied)

Bartone’s passion for medicine was initially inspired by his family doctor, Vic Buccheri, who became his mentor and a formative influence.

“With both my parents being ill, seeing the help they received from doctors and the health system made me want to help people,” he says.

He describes the years following his graduation from the University of Melbourne as “exciting”, despite the 90-hour working weeks as an intern in a hospital and the pressure of new responsibilities.

Bartone’s first Christmas working as a doctor was in Sale, in the Gippsland region, and he was away from his family for 26 days straight.

While his first Christmas away from home was tough, Bartone explains that travelling was part of the job and soon became “the norm”.

Bartone’s first clinic was in the house that he was living in at the time, in Keilor Downs.

“Within a few months the clinic was so big that we had to move out of the house,” he says.

Over the years, Bartone has established himself at a national level, holding the title of president of the AMA from 2018 to 2020, after having held the position of vice president from 2016.

Before that, he was elected as vice president of the AMA Victoria in 2012, and president in 2014.

Today, the passionate doctor is still active in the field, doing media commentary and running two clinics, in Lalor and Niddrie.

His three children have chosen to follow in their father’s footsteps: his eldest, Anna, is a biomedical engineer; his son, Francis, owns a gym and is an exercise trainer and advisor; and his youngest, Elizabeth, is in her final year of her master’s degree in public health.

“They’re all very strong-minded and when we get together for lunch or dinner it’s very hard to get a word in,” a proud Bartone says with a smile.

Bartone was far from surprised by the recent COVID-19 outbreak in Victoria; during an interview with Il Globo last month, he had stressed the importance of wearing a face mask to prevent further outbreaks.

“Now, we’re potentially in a lull and have a false sense of security; it’s not finished,” he says.

“But if you go out in public, people are carrying on as though it’s over.

“People like me are worried that the next lockdown will be sooner rather than later.”

Bartone praises the work of the federal government and Health Department Secretary Brendan Murphy at the start of the pandemic, for recognising the danger and acting immediately.

He spoke more harshly, however, of the Australian health system with regards to its lack of empathy towards the elderly, referring to his mother who passed away last October in an aged care home in Melbourne.

“My mum had lots of medical conditions; she had very significant osteoarthritis and osteoporosis,” he says.

“She was always destined to suffer with pain but she did nothing in terms of physiotherapy or rehabilitation to help herself.

“My father was the only one able to push her to take care of herself, but he passed away 12 years ago.

“During COVID-19, not seeing her children every day was tough.

“I could get into the aged care home to do a mental health visit but the others couldn’t.

“My sister went to Sydney for work and she got stuck there... she didn’t get to see our mum’s funeral.

“My mum didn’t get COVID-19 but it made it very difficult to get help; other medical issues weren’t being addressed in the hospitals while COVID-19 was killing people.

“Mum didn’t cope with the extreme conditions: the loneliness, the isolation and the pain.”

The last photo of the Bartone family with Tony’s mother. (Photo supplied)

Bartone describes having to organise his mother’s funeral and decide which 10 guests should be able to say goodbye as “the worst thing in my life”.

He hopes that society won’t let such tragic circumstances happen again and cannot fathom why such a wealthy country as Australia does not do more for its elderly citizens.

“If I could change anything, I’d have aged care facilities with clinics inside,” he says.

“For me, the healthcare system is at a crossroads; we need to invest, because we’re all getting older and living longer.

“We need to look after the people who don’t need to be in an aged care facility and support them to stay at home.

“CO.AS.IT., for example, does a fantastic job but it doesn’t receive enough funding or have enough people to help.

“It’s a disgrace that we, as such a developed and rich country, can’t look after our elderly citizens.”