Poignantly personal stories of migrant women have been published as part of the Victorian Seniors Festival Reimagined 2021.

These stories about women, arts and activism come from women of Chinese-Taiwanese, French-Canadian, Greek-Cypriot, Indian-Malaysian, Italian, Maltese, Nigerian and Sri Lankan heritage.

They reveal historical events that had a significant impact on their life before and after coming to Australia.

Published in pairs for each episode titled ‘Women, Art and Activism’, these podcasts are a true example of social inclusion within cultural diversity.

Award-winning writer and researcher, Lella Cariddi, personally curated the online series.

“These are heartfelt stories that seek to broaden the conversation about our heritage, the circumstances that brought us and/or our ancestors to Australia, how Australia has changed us and how our contributions have influenced societal changes,” Cariddi said.

In the fourth episode of the series, Italo-Australian artists Wilma Tabacco and Liliana Barbieri take us back to their early years in Abruzzo, touching on the dramatic impact of their adoptive country, the social constraints handed down from generation to generation and the extreme courage that has guided them on their personal and artistic journeys.

“A few months ago, while channel-surfing, I happened upon the last stages of the Giro d’Italia and the cyclists were climbing the central mountains towards the finish line at Campo Felice,” Tabacco said.

“I froze before any announcement was made as to the location of the cyclists; I recognised the landscape by an inexplicable emotional response and then by sight.

“Campo Felice is in the central mountains of Abruzzo, close to where I was born and where I enjoyed many excursions with family and friends.”

The artist was born in Fagnano Alto, in the central Italian region of Abruzzo, where she lived for the first four years of her life, surrounded exclusively by women; her father had already travelled to Australia to seek his fortune.

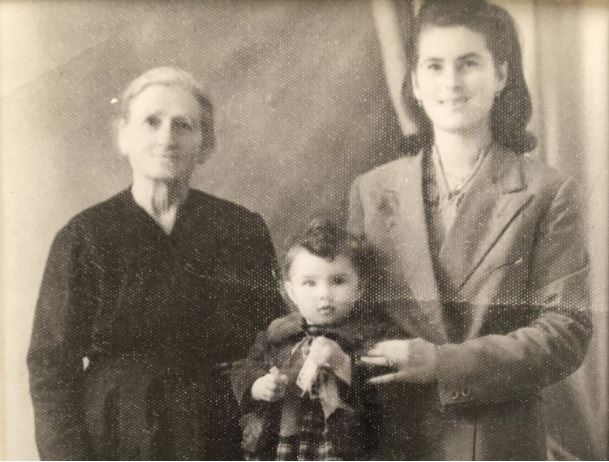

A young Wilma Tabacco with her mother and paternal grandmother in Italy

“The small villages in the central mountains were inhabited by women and abandoned by men, husbands, brothers and cousins who’d left in search of employment overseas and never returned.”

Tabacco first met her father when she migrated to Australia.

Upon their arrival in their new home, the Tabacco family faced the dilemma every migrant does: becoming “Australianised”.

“Were my parents happy to be Australians, Italo-Australians? No, yes and maybe,” Tabacco said.

“My parents’ aspirations for me were not mine: a steady job, suitable for a woman – a secretary perhaps – early marriage and children.

“Art? That was for losers.

“I managed to convince my parents that I should go to university and study something really useful like economics.

“Next came a diploma in education and a very secure teaching position at a high school.

“If I inherited anything from my father it was his stubbornness; after a few years I ran away to Italy, living with my maternal aunts and cousins on and off for a year and travelling around Europe in between.

“My relatives loved me but considered me most peculiar: a young woman travelling on her own, so far from home, who looked different, dressed strangely and spoke Italian with an unrecognisable accent.”

Tabacco’s overseas adventure inspired her to pursue a career as an artist.

Since then, she has participated in more than 200 group exhibitions, nationally and internationally, and 40 solo exhibitions.

“I was born during an earthquake; the village was evacuated except for my mother, paternal grandmother and the midwife,” Tabacco recounted.

“That shake up contributes to my appetite for catastrophes: earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the demise of civilisations.

“I wore strangely coloured clothes as a child but I didn’t know then that colour aesthetics is a cultural construct.

“You want to see strange colours? Look at my 1990s or 2000s works: nasty, straight combinations of unlikely colours and forms designed to cause uncontrollable optical vibrations, disorientation and sometimes – I’m told – migraines.

“I have a strange name, I’m a woman and I prefer to remain elusive and independent.

“I live in Australia and I’m very happy here, but I was born in Italy and I can’t change that.

“Am I Australian? No, yes and maybe.”

Fellow artist Barbieri arrived in Australia from the tiny hilltop town of Ripa Teatina, in Abruzzo, making the 28-day voyage by ship with her mother.

Her father had migrated to Australia in 1954, with the rest of the family following 10 months later.

“My mother’s determination to make a success of her new life in a foreign land is inspirational,” she said.

“Friends had assured her that there was work to be had for anyone with dressmaking skills.

“Within three days of arriving, she had carefully folded the nine-penny fare into a handkerchief and climbed aboard an early morning tram bound for Flinders Lane in Melbourne’s CBD, which was the centre of the ‘rag trade’ in the mid-1950s.

“Full of hope and great trepidation she found luck behind the third door she tried.

“She was escorted to a sewing machine, and through the use of sign language, was asked to put together a garment from start to finish… and she was hired!

“Later that day, she returned to our boarding house in Brunswick elated by the promise of her own pay packet at the end of each week.”

Barbieri’s love for travel led her to her first career in international aviation, and she was employed by Italian flag carrier Alitalia.

“In the days before Skype and Zoom, we actually flew to Rome regularly for training and meetings,” she said.

“It was a rather flamboyant lifestyle; I happily flew around the world as part of my job.

“Those numerous trips to Italy served to fuel my fascination for all things Italian and heightened my awareness of the beauty of art, design and architecture, especially the work of the great masters of the Italian Renaissance.

“Not surprisingly, my family questioned my sanity when I announced I was giving up an established career to follow my first love and take up full-time studies in fine art.

“My childhood dream to become an artist had never diminished and was now knocking rather loudly on my psyche.

“By the time I ditched the corporate world I had two teenage children, a husband and a mortgage; it took enormous courage to make such a drastic change in direction!”

After she completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Master of Arts by Research at RMIT, Barbieri’s artistic career took off.

“Each day presented opportunities for creative conversations, collaborative works, planning exhibitions and an ongoing engagement with Melbourne’s artistic community,” she said.

Barbieri’s work has made its way into galleries, museums and private collections in Australia, Beijing, New York, London, South Korea and Italy.

In recent years, her time has been divided between private practice and lecturing at various tertiary institutions, in Melbourne, Hong Kong and South Korea.

The artist firmly believes that the decision to pursue her dream changed the family culture in which she grew up for the better.

“I continue to exhibit regularly, but over this protracted period of COVID-19, I’ve become obsessed with the beauty and transformative power of one of nature’s most amazing creatures, the butterfly,” she concluded.

Liliana Barbieri’s latest work in lockdown

“Being unable to access my studio during lockdowns, I’ve scaled down my work to fit on a kitchen table and I happily spend hours creating great swarms of delicate hand-painted, hand-cut butterflies that flutter in the tiniest breeze.

“Conceptually, the butterfly presents a perfect metaphor for fragility, strength, freedom and metamorphosis and, just like people and ideas, butterflies have the ability to migrate across many boundaries towards a common goal.

“My dream today is that human societies will embrace a paradigm shift in thinking following this wakeup call and that, just like the butterfly, Planet Earth may experience a positive transformation.”