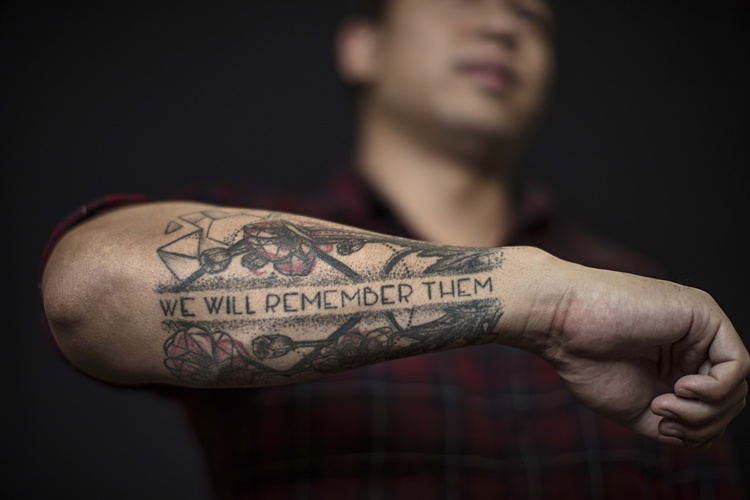

Many members and veterans of the Australian Defence Forces have tattoos, and while their reasons for getting tattooed are as varied as the people themselves, self-expression and belonging play a part.

They also share a common purpose in getting inked: to remember.

The Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra last week launched a multimedia exhibition which tells the stories of modern veterans and their families, who through their tattoos commemorate the people, events and experiences that have shaped their lives.

Running until January 2021, Ink in the Lines features more than 70 portraits and details the experiences of 21 Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

Throughout 2019, photographic curator Stephanie Boyle, photographer Bob McKendry and videographer Stephen Toaldo set out to capture their personal stories.

The son of Venetian migrants, Toaldo worked in television for decades before becoming the AWM’s multimedia production manager three years ago.

Ink in the Lines took Toaldo and his colleagues all over the country and into the homes of veterans and their families to give them an insight into intensely private experiences that many had never shared before.

“We were honoured to hear their stories,” Toaldo said.

“There were lots of tears as well as laughs and it was often cathartic for them.

“One man was telling his story and his family were behind me in tears because they’d never heard any of it before.”

Whether it’s a small inscription on one’s foot or a full body of ink, there’s a deeper meaning behind the tattoos of military personnel, which extends far beyond a fashion statement.

Military men and women can be profoundly affected by their experiences of deployment, including: personal joys, such as the friendships that form in teams and units; hardship, such as separation from home; or tragic loss, such as the death of a friend.

Many turn to tattoos to process and embody these experiences and emotions.

One of the most poignant stories Toaldo heard was that of Adam, a veteran who has many tattoos to signify his military experience, including one on his chest in honour of his friend David “Poppy” Pearce.

Poppy was killed by an IED blast in Afghanistan in 2007.

Adam and Poppy had deployed to the Solomon Islands together, and Adam helped Poppy to go from reservist to full time in the army.

“Adam sent Poppy a message telling him to be safe; unfortunately, Poppy never got the message,” Toaldo said as he choked up.

“Like a lot of veterans, tattoos are therapy for Adam.

“It can be very painful at times, but Adam says he’s here to tell you it hurts and some of his friends haven’t been so fortunate.”

Adam has a tattoo on his chest in honour of his friend David “Poppy” Pearce. (Photo: Bob McKendry/AWM2019.289.504)

Another veteran Toaldo and his team spoke with had deployed to Somalia when he was just 19 years old, as part of the 1992 – 1995 operation to provide relief from civil war and famine.

“He’d never even heard of the place,” Toaldo said.

“He got to Somalia and he’d never seen a dead body in his life.

“Within minutes of getting off the boat, he saw hundreds of bodies.

“He certainly didn’t sleep that night, or the next few nights.”

The exhibition is divided into four COVID-safe sections that explore the themes of: identity and belonging; mateship and family; loss, grief, anger and commemoration; and, lastly, healing.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic and travel restrictions, the AWM has provided access to Ink in the Lines online, as well as a range of information and content related to the exhibition, including images, articles, podcasts and vodcasts.

The AWM hopes to eventually tour the exhibition nationally, and is still welcoming stories and photos that will be compiled for the purposes of an archive.

Toaldo said the exhibition and project at large is “all about understanding and remembering”.

“These people are everyday people who have done extraordinary things in their lives,” he added.

“I think Australians sometimes forget the value of people who serve.”

The exhibition is not only for the general public, but for those behind the stories themselves.

“Some of the people involved who have suffered and still suffer from PTSD and haven’t left their homes for quite a long time have now said they want to come and see the exhibition,” Toaldo concluded.

“The response still brings a tear to our eyes.”

For more information on the Ink in the Lines exhibition or to view related, articles, podcasts and vodcasts, visit the Australian War Memorial’s website.