The narrative is presented through the perspective of a young boy, illustrating how he navigates the complexities of an adult world shaped by migration and its effects on migrants and subsequent generations. The storytelling effectively integrates Giovannoni’s own autobiographical elements with fiction, creating a highly captivating and nuanced tale which is likely to resonate with many readers.

“We always hear that people came to Australia for a better life,” Giovannoni explains, “This doesn’t mean that is what they experienced, but we don’t always talk about this aspect.” This is the premise for the story.

The novel opens with a vignette - No relatives living, friends informed. It describes the death of a young Italian migrant, Luigi, who is killed by a petrol drum explosion on a tobacco farm. The drum had been set up to boil water to humidify the cured tobacco. The gathering the remains of Luigi’s mutilated body is even more unsettling as the 28-year-old is reported to have no relatives. No one to contact who might mourn his death. The official report states: “Nothing found in possession, but suitcase of private papers taken from hut and hut locked.” The suggestion is that another Italian immigrant with a heart full of hope ends up being a mere reference within the recollections of old folk - until their stories also disappear.

Set amongst the burgeoning tobacco farm industry in fictional Victorian town of Mitrefo`, there are many Italians who arrive with their cardboard suitcases to take Luigi’s place. Giovannoni describes the harsh reality of tobacco farming in a land that is dry and where conditions are unforgiving.

The boy’s family set out to create something of the land and their lives, like so many other Italian tobacco farmers, through sheer hard work. As more Italians arrive, a community forms.

Italians in Mitrefo` begin to recreate cultural traditions from their villages. A cinema and concerts bring the community together, while a café opens for card games - just like in Italy.

Italians representing various regions all over the peninsula come together with the shared hope of a ‘better life’. Campanalismo is put aside, they are all foreigners to the ‘colony’.

Giovannoni uses the term colony frequently in the novel. He explains that this is a term used by his uncle Paolo who lives in San Ginese. Giovannoni dedicates the book to his uncle with whom the author shared a special bond. “My uncle would always remind me that we live in what was, and remains, essentially a colony,” says Giovannoni, “One where the Queen dismissed the elected prime minister.” One also where, in the novel, the Australians get together on “what they call Australia Day”; a day with citizenship ceremonies where Italians opted to be naturalised and adopt names that were easier to pronounce in the colony.

The “othering” between Australians and Italians is a fascinating leitmotif in the novel. When the local doctor’s daughter marries “an undeserving immigrant … It is a breach of the Australian wall.”

Giovannoni uses imagery to highlight complex themes. For instance, the café is taken over by Italians. An indicator of successful settlement and social mobility. The café ‘clientele changes, they are Italian. The community now have a place to socialise and enjoy their own style of refreshments.

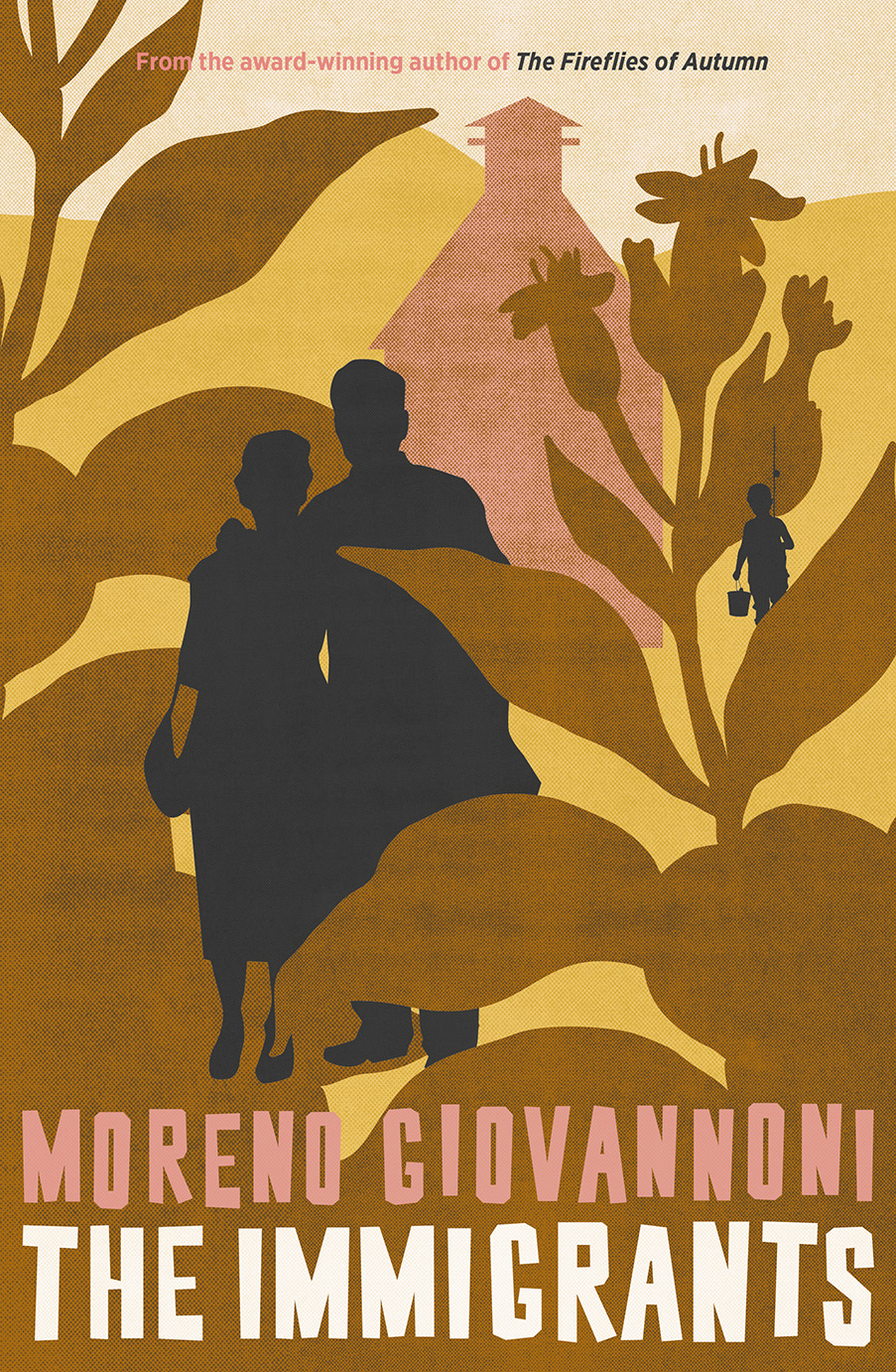

The cover of The Immigrants: Fabula Mirabilis

The café` is distinguished by two large murals. The original mural depicts an Aboriginal man, “his raised left leg strategically positioned for modesty, with his left foot resting on his right thigh, about to launch a spear at a kangaroo who is facing him … the kangaroo has tears streaming down its face”. The second mural is of St. Peter’s Square featuring the Basilica and “statutes of saints mounted on the colonnade”.

The storytelling is powerful, evocative and painfully honest. The story is told in seven parts, each punctuated by a grotesque, a vignette of human tragedy that defines a particular immigrant experience. The number seven, as the author explains, is not accidental. The number of grotesques suggest a biblical reference.

The significance of each grotesque lies in their resonance with readers of the subsequent generation. These stories resemble those recounted quietly by parents and relatives during reflective moments, episodes ingrained in the narrative of Italian migration to the colony but not commonly shared publicly.

In this way, Giovannoni brings forth these stories and the harshness of sacrifice and loss behind the tagline “I came to Australia seeking a better life.”

The stories are those that Giovannoni heard growing up and through his subsequent visits back to Myrtleford in the northeastern region of Victoria. The pandemic period provided him with an opportunity to write and undertake research. He scoured Coroners’ reports and followed people’s journeys through details available through the State Archives in North Melbourne to piece together details which formed the basis for planning this novel.

“It’s only my second book,” Giovannoni points out, “I don’t know how to write a book. I know I should start off with a bang and end it well too. That’s the advice of my publisher.

“In fact, I had both bookends ready before I even began writing the rest of the book.”

For someone who feels they do not know how to write a book, Giovannoni has again presented the reader with an unforgettable literary experience. He carefully curates the story of the boy against a menagerie of migrant experiences and weaves a captivating and fiercely frank account of immigration to the colony.

Love, pathos, empathy, bitterness, loss, hope – the storytelling provides a sense of the depth and complexity of human experience.

Giovannoni uses the names of his own parents for two main characters in the novel, Ugo and Morena. A way of maintaining connection with the inspiration for the story.

He fondly remembers his parents: his father was both dapper and charismatic, and his mother was determined, pretty and loving. Both were stylish and meticulous about their appearance.

In the book, the Italians are derided for their stylish clothes. Men are thought to be ‘effeminate’. The book includes small details, attesting to Giovannoni’s mastery in presenting seemingly nondescript details for the reader’s consideration. For instance, the boy’s father packs a pair of two-tone black and white lace-up shoes that were handmade in San Ginese. These shoes end up being worn by the boy to collect eggs and tend to the chickens on the Mitrefo` farm. They are useless otherwise.

Against the harshness of migration and the gruelling tobacco farm work (that literally sends people crazy), the next generation grow up. The children navigate the two cultural realities as best they can. They find their places of peace. For the boy, it is through fishing: “March flies, snakes, a dog, a horse, a fishing line.” The boy’s childhood is narrated through a tone of distant but gentle empathy.

The boy seeks moments to be alone with his meanderings, rather than take up footy or cricket. Moments to be a child in an adult world of work, migration and, at times, parenting parents.

Through the boy, we learn of the experience of being a return migrant. His parents take the family back to San Ginese. The boy then finds himself surrounded by a village full of people who all know him and speak the same dialect. They are the same, yet different. The enduring connections of family and kin are not severed by time and distance. These connections provide a warmth and vitality, but also complicate the migrant experience so that home is never easily identifiable.

Giovannoni’s writing craft is simply powerful.

Of course, Giovannoni’s writing talent has already been well established through his award winning first book, The Fireflies of Autumn, which received the inaugural Deborah Cass Prize.

Giovannoni came to writing in his 60s, a period in life that provided scope to collate both sets of his notes – made up of thoughts and writing aspirations - into his first novel. Prior, he worked as an interpreter and translator. One wonders if this professional role provided him with the opportunity to carefully note the humanness behind the translated words. Certainly, the author has a particularly captivating and frank writing style which closely echoes a type of conversation between the reader and the narrator.

Giovannoni’s motivation in writing the book was to preserve the stories that “need to be told before they disappear”, just like Luigi, the character of the first grotesque. They are stories that present the “the other story, the one that doesn’t get told about the Italian community, who migrated to Australia”.

The author hopes that readers might draw on the insights of the story to consider the migration experience and relate it to those they may know – “the widow next door, their nonni, the family who you think you know but are not who you think they are – their story behind the better life story”. He also hopes it resonates with all migrants by sharing underlying commonalities which make up a shared experience.

The Immigrants, Fabula Mirabilis (published by Blacinc Books), will be officially launched on Tuesday, July 1 at 6:30 p.m. at CO.AS.IT. (199 Faraday Street, Carlton).