Poverty never really left him, but simply changed its face, its language, its continent. It was once the cold of public housing without running water, barely enough bread on the table, clothes passed from one sibling to another.

Later, it became the quiet humiliation of feeling like a foreigner, the weight of discrimination, the frustration of not having the words to fully express yourself.

Today, that same poverty returns in the eyes of the children he meets each day: in empty stomachs before school, in families unable to pay the rent, in childhoods that end too soon.

Pietropiccolo did not study poverty—he lived it in post-war Italy, the kind that never makes it onto postcards.

“We were incredibly poor,” he recalls, visibly moved. “We lived in public housing with two bedrooms, five or six of us, no running water and no heating. There was very little food and very few clothes.”

His father, Maturino, worked sporadically as a farm labourer, often for extremely low wages and sometimes without pay from landowners. His mother, Giovanna Marchesani, washed clothes for neighbours, frequently receiving only food or second-hand garments in return.

Around them was a country scarred by war, with damaged homes and a shattered economy.

For many families like theirs, leaving was not a choice but a necessity. Theirs was a poverty woven with dignity, marked by silence and departure.

Perhaps that is why, for almost fifty years, Pietropiccolo has chosen to stand alongside those in need without turning away—first as a migrant, then as a social worker, consultant to the Children’s Court of Western Australia and finally as the director and founder of initiatives that have consistently called for radical change.

In 1956, his father was the first to leave Italy. It was an enormous sacrifice. “He never really liked living in Australia. He always felt the pull of Italy,” Pietropiccolo says.

“He literally lived in a tent in remote areas of Western Australia to save enough money so we could all join him.”

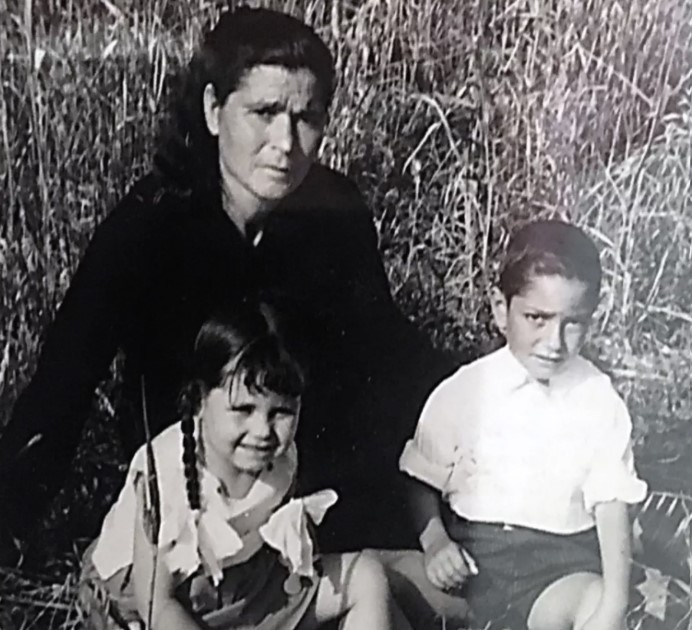

Pietropiccolo (right) with his mother, Giovanna, and sister, Maria, in their hometown of Ortona in Abruzzo before they moved to Australia

That same year, Tony began school in Italy, fortunate to grow up in a close-knit community and form friendships that would last a lifetime.

For his mother, migration was an appealing prospect; in Australia she would join a brother, a sister and several cousins, hoping to secure a better future for her children.

On September 3, 1960, they left Ortona, the picturesque town in the province of Chieti, boarding the ship Neptunia. “With my mother and my sister Maria, we arrived in Fremantle, Western Australia, on September 28 that same year. Those are dates you never forget,” he says, his voice catching.

It was a completely new world, and not an immediately welcoming one. Australia felt vast and distant, offering wary glances and heavy silences. New arrivals had to prove they deserved space, voice and opportunity in a country that demanded much and gave slowly.

“It was a real culture shock,” he explains. “Not just the language—everything was different: clothing, food, even sport like cricket and football, which we had never seen.

“There was a lot of discrimination, a lot of negativity towards new arrivals, especially Italians.”

At school, there was no structured support, no assistance with learning English or feeling included. “You had to fend for yourself,” he recalls.

Italian children gravitated towards one another for protection. In Fremantle, the presence of a large Italian community softened the blow. Everyone was facing the same challenges, trying to find their bearings in a foreign land. There was a strong sense of solidarity. “That allowed us to keep our identity intact,” he says.

Pietropiccolo (second from left) holds the Premio 28 Dicembre di Ortona in front of the council house where he lived as a child. With him are his childhood friends (left to right) Nino Valente, Tony Pietropiccolo, Tommaso Iurisci and Corrado Ciavalini

There was no need to renounce their roots. For Pietropiccolo, it was possible to be both Italian and Australian—yet the wounds of discrimination never fully healed.

“They have had a lifelong impact,” he admits. “But they never stopped me from contributing to Australian society.”

Over time, his mother also found work in a restaurant to help support the family. It was a simple life—no holidays, no travel. Just hard work, sacrifice and careful financial management, which eventually enabled his parents to buy a house and provide “the essentials”.

“We didn’t have anything special, but we had everything we needed,” he says.

After finishing school, like many others, he found himself at a crossroads. His interest in social issues led him towards social work and psychology. Two degrees later, his calling was clear: to work alongside the most vulnerable and to question the social structures that produce deep injustice.

In 2016, he founded the Valuing Children Initiative, a project aimed at overturning the common view of childhood care as merely “an investment in the future”. Children already participate in society every day through their presence, their ideas and their unique perspective on the world.

Yet despite Australia being one of the wealthiest nations globally, child poverty remains a largely invisible emergency. According to the Poverty in Australia 2025 report, around one in six Australian children lives in poverty.

Affected families earn on average 44 per cent less than the median income, facing daily food insecurity, housing stress and limited access to essential services such as education and healthcare, largely due to housing costs and inadequate public support.

“There is a belief that if you’re poor, you’re not trying hard enough, that you don’t deserve help. That makes any discussion about poverty politically difficult,” Pietropiccolo says.

In response, the End Child Poverty campaign (backed by more than 180 organisations and children’s commissioners across the country) is calling for national legislation to define and systematically address child poverty, recognising it not as an individual problem but a societal one.

Tony Pietropiccolo with the mayor of Ortona, Angelo Di Nardo, in front of the council house where he lived as a child

Every day at Centrecare, the not-for-profit community services organisation he has led for 37 years, Pietropiccolo witnesses the vulnerability of young people within a complex society that too often get forgotten.

“Whatever you do, you are never alone,” he says. “We have more than 300 staff in our organisation and recently developed around 63 services across Western Australia—supporting people experiencing homelessness, separated couples, those facing psychological, family or financial difficulties.

“It’s enormous work and only possible thanks to extraordinary people and institutional support.”

Pietropiccolo was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his work with vulnerable communities and for creating programs to improve access to affordable housing and promote the wellbeing of Aboriginal people and refugees

“I have always believed nothing is achieved alone,” he shares, “Every personal recognition is only part of the story. It reflects the contribution of my parents, friends, teachers, colleagues and many others.”

His commitment is deeply rooted in childhood and in his dual cultural identity—Italian and Australian—which he carries as both richness and wound.

“When I’m in Italy, I’m seen as Australian. When I’m in Australia, I’m seen as Italian. As a migrant, you live permanently between two worlds,” he reflects.

Returning to Ortona each year is more than a visit; it is an act of reconciliation with the child he once was—poor, migrant, searching. It’s reconnecting with old friends, sitting in the courtyards of the public housing where they grew up, remembering that belonging does not disappear, even when life takes you far away.

It was one of those childhood friends, Tommaso Iurisci, who nominated him for the Premio 28 Dicembre Città di Ortona, the city’s highest civic honour, awarded annually to mark the anniversary of Ortona’s liberation in 1943 and recognising citizens and organisations distinguished by commitment, culture and service.

The award honoured Pietropiccolo for his leadership and decades-long dedication to social justice and vulnerable communities. His journey, from modest beginnings in Ortona, stands as a testament to the power of compassion and perseverance.

Tony Pietropiccolo (centre) receives the Premio 28 Dicembre di Ortona in front of the black and white photo of him with his mother and sister

“My father always spoke to us about Ortona—the beauty of the maggiolate, the music and, of course, the vineyards,” recalled Pietropiccolo during the award ceremony.

“His love for this land became ours, despite the thousands of kilometres between us.

“Receiving this prize feels like a dream. It honours not only me, but also the support and care I have received from my family, especially my wife Vicki, and from my friends and colleagues.

“Aboriginal Australians speak of returning ‘to country’, the places to which they feel a special connection. I return often to Ortona, because this is where I return to my own ‘country’. This is where I reconnect with an important part of my life.”

Even today, Pietropiccolo carries within him the ten-year-old boy who left his hometown to face the unknown.

Returning to Ortona, sitting with school friends in the courtyards of their childhood, “having a coffee together”, is for him a true return to childhood—a moment when past and present intertwine, and the sense of belonging becomes unmistakable.