The bridge was intended to be an architectural masterpiece and a point of pride for Melbourne that rivalled the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

But two years into its construction, it became the site of Australia’s worst modern industrial accident and a transformational moment in Melbourne’s history.

The avoidable tragedy killed 35 men, widowed 28 women and left 88 children without fathers.

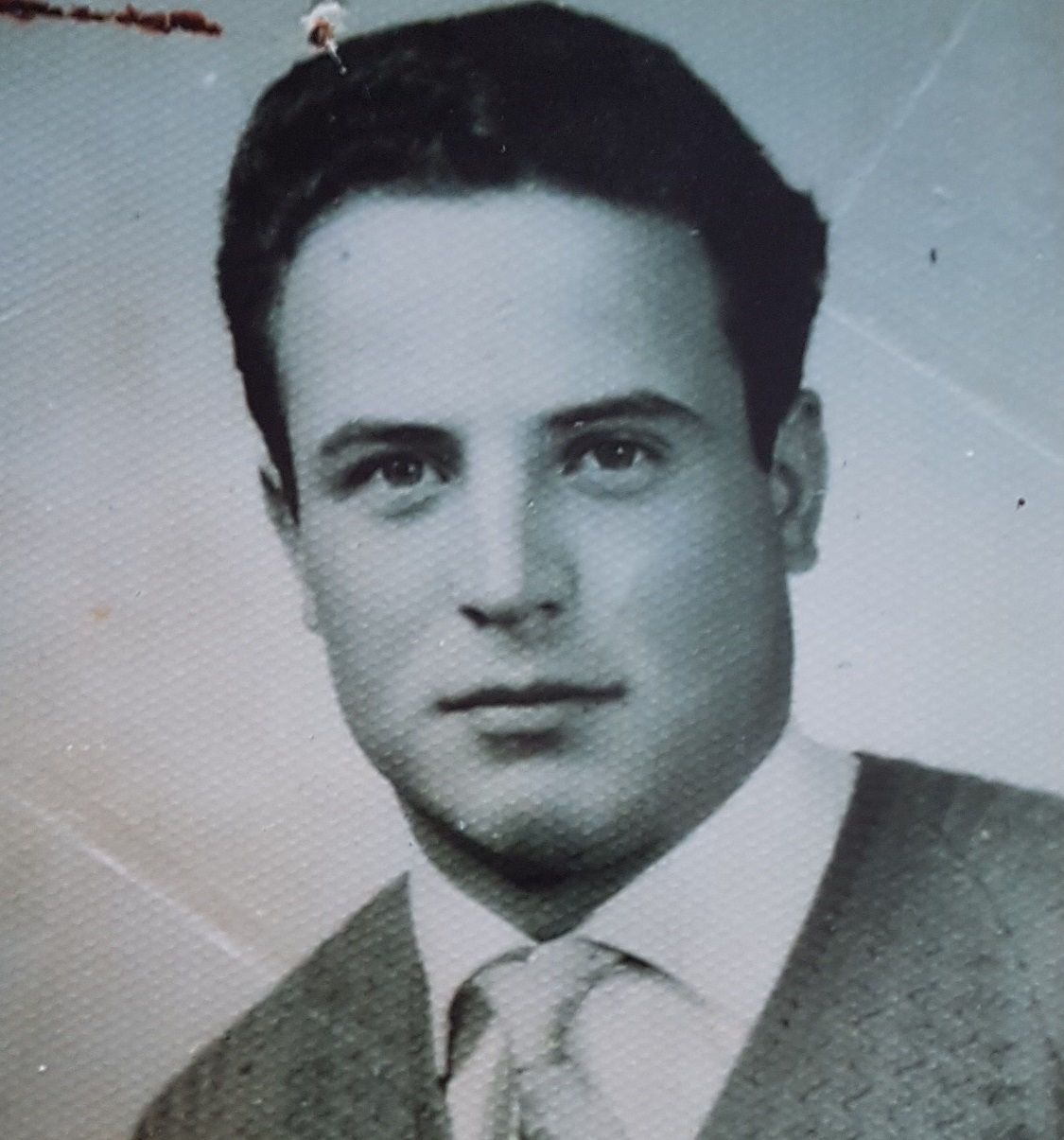

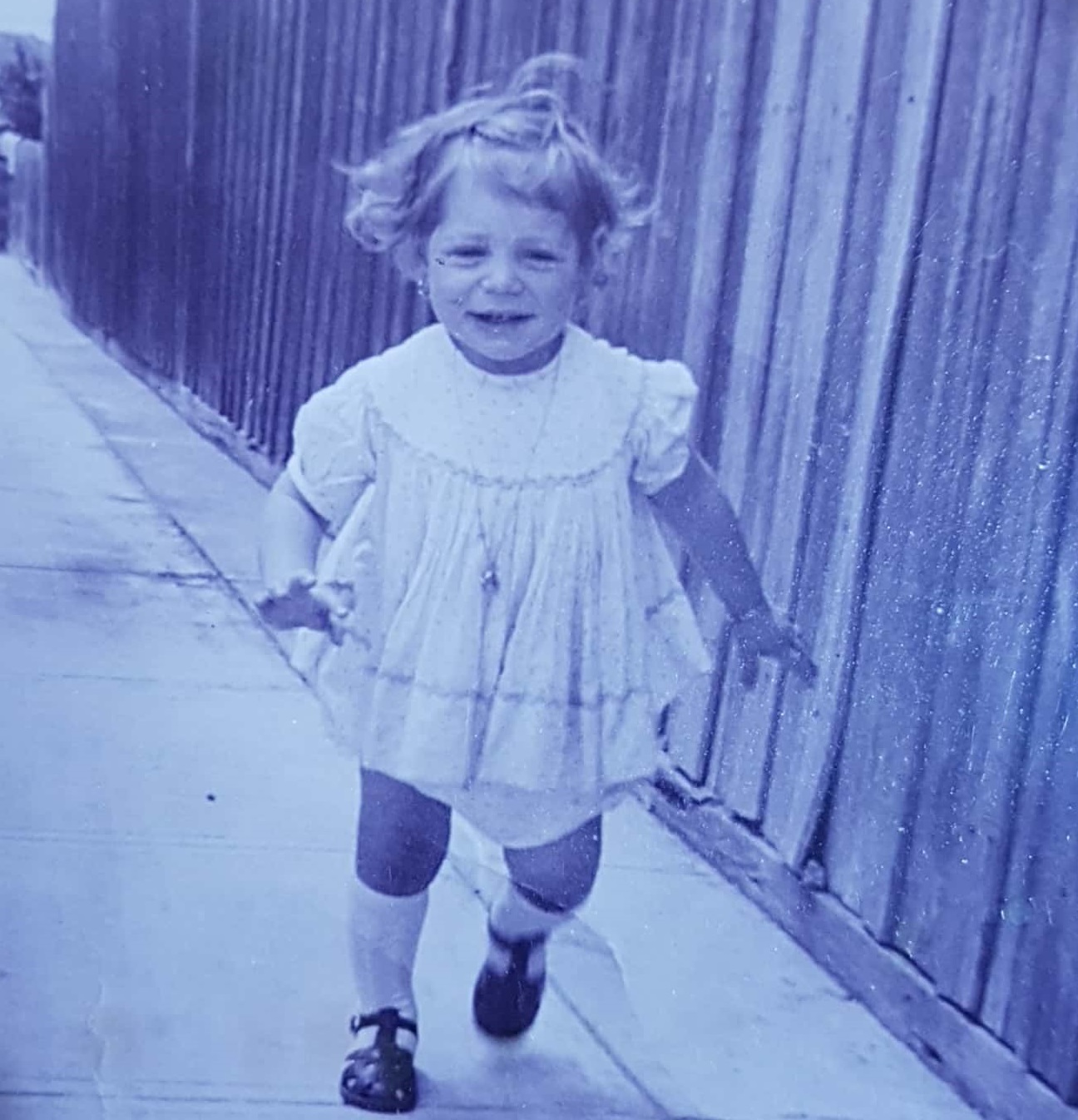

One of those children was 18-month-old Antonietta Piermarini, who would go on to grow up without a single memory of her father, Frank Piermarini.

Frank was born in the Umbrian city of Perugia and migrated from Italy to Australia in the mid-1960s.

A few years after his arrival in Melbourne, he began working as a rigger on the West Gate Bridge.

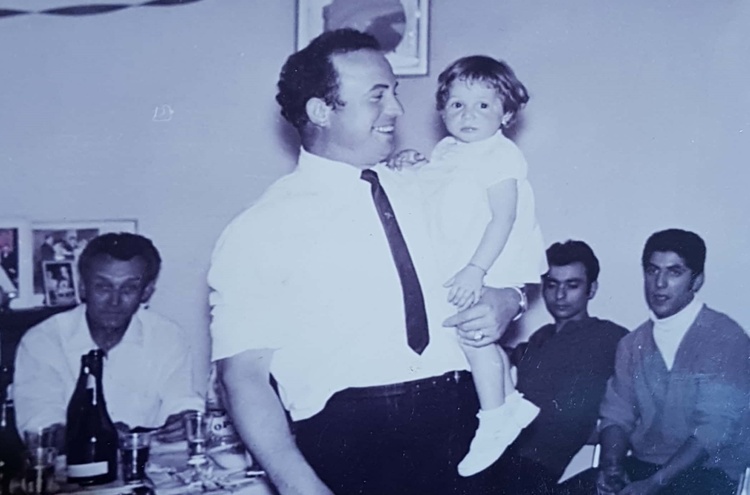

“My father was a caring, kind, genuine, honest gentleman who always had a smile on his face and was very well liked by everyone who met him,” Antonietta said.

“I’ve been told by people who knew him that he was a doting father and that he truly adored me.”

Every day, Frank went to work with the intention of coming home to his wife, also an Italian migrant from Calabria, and their baby daughter.

The morning of October 15, 1970, he left for work, like every other day.

At 11:50 am, just before what would’ve been his lunch break, the West Gate Bridge suddenly groaned.

An eerie pinging noise filled the air and the girders started to turn blue under the pressure.

A 2000-tonne span collapsed without warning, crashing on to the western bank of the Yarra River below.

Within a matter of minutes, chaos ensued.

Some lives were stolen and others changed forever.

Anonietta’s mother was working at a knitting mill in Northcote when the incident occurred.

The other women at the mill heard news of the collapse on their transistor radios, and immediately asked her: “Where does your husband work again?”

“No one said anything else to her but then she received a phone call from her mother telling her to go straight home,” Antonietta said.

“Apparently the Salvation Army had turned up at my grandmother’s house to offer assistance if we needed any.”

Frank miraculously survived the initial collapse, but it left him with a broken back.

“I’ve been told that when he was found after the bridge collapsed, he was more concerned about the other workers and their wellbeing than himself,” Antonietta said.

Frank was rushed to the Royal Melbourne Hospital where he remained for 10 weeks.

He passed away from internal injuries on January 2, 1971.

He was just 32 years old.

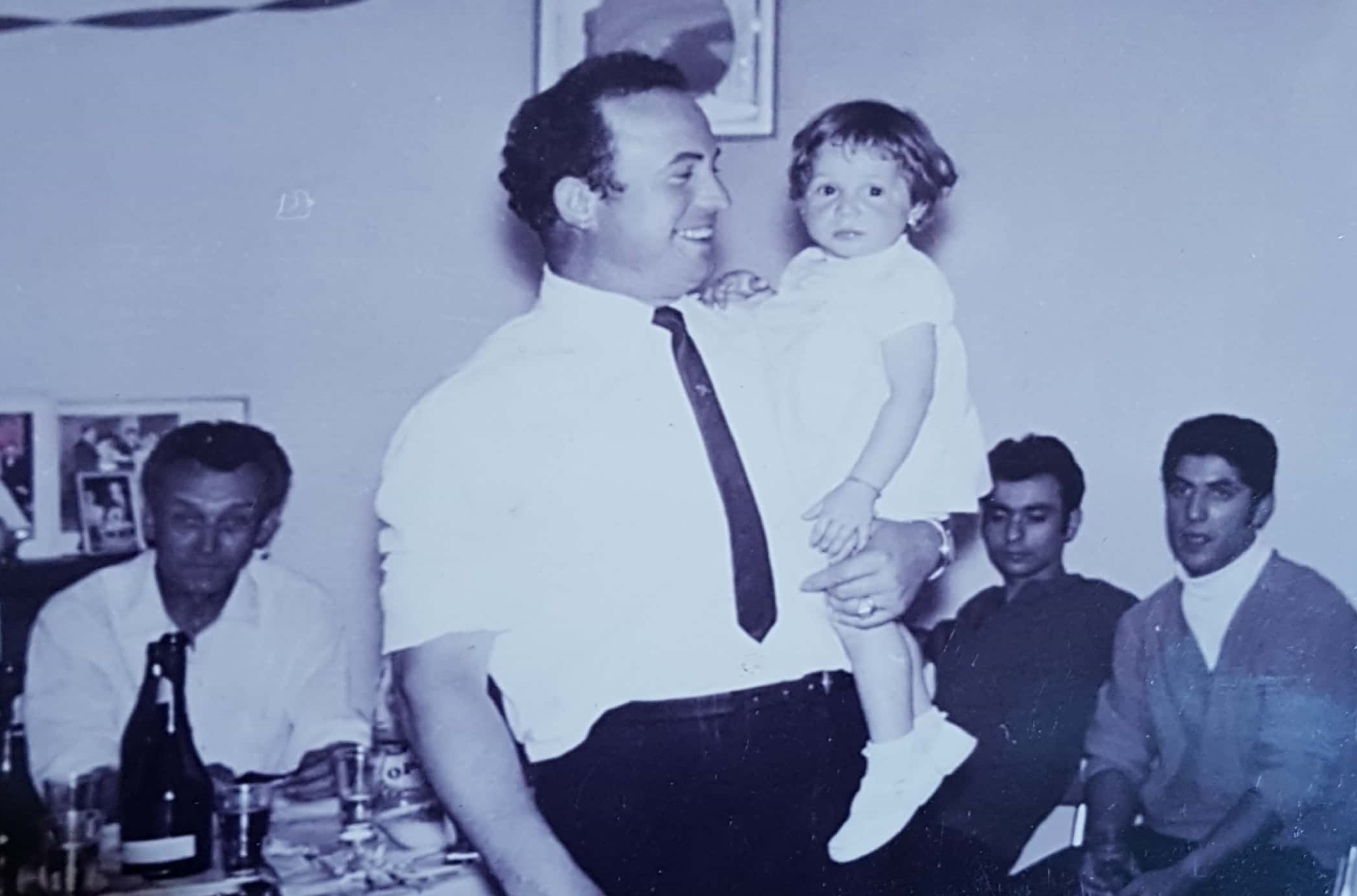

An image of Frank Piermarini

Frank’s sudden death had an immense impact on his loved ones and was a catalyst in changing the future of his daughter, whose life had just begun.

Antonietta said the loss of her father ultimately caused the complete breakdown of her family.

“It was hard growing up,” she explained.

“My mother later remarried and I had a half-brother; my stepfather was a good man, but I always felt different.

“When my father passed away it was like I lost both parents, because I endured 20 years of trauma from my mother.

“The closest person I had to a mother was my maternal grandmother Maria Angela; I was very fortunate to have her in my life.

“She passed away when I was 15 years old and I was devastated.”

Today, Antonietta is estranged from her mother and they haven’t seen each other in two decades.

“I feel like an orphan in a way... I don’t have anyone,” she said.

“I suffer from mental health issues and it’s been an ongoing thing in my life.

“I see a psychologist on a regular basis and we talk about my father’s passing a lot.

“She says that losing my father at such a young age, even though I don’t remember, was a drastic, traumatic incident for me.

“Then to endure my mother’s trauma has had a big impact on my life.”

Up until Thursday, when Antonietta featured on the documentary West Gate Bridge Disaster: The Untold Stories, which aired on Channel Nine in honour of the 50th anniversary of the bridge’s collapse, Antonietta had never spoken publicly about her experience.

“I’m normally quite a private person but I chose to speak out to honour my dad and acknowledge the loss of me not having him here,” she said.

“The documentary and this interview are like closure for me and they’ve helped me deal with it a little bit better.

“I thank Shane Jacobson, Nicole Bardy and all the crew for the making of the documentary.”

While Antonietta is currently doing well and has a strong support network around her, she often wonders what her life would’ve been like if her dad was still around.

“It’s been sad that I haven’t been able to spend my life with him,” she said.

“But I’m very happy to say that I’ve always felt his presence around me and that’s been a comfort to me.”

An image of a young Antonietta Piermarini

What cuts even deeper for those affected by the bridge’s collapse is that it was preventable.

In fact, the workers had previously gone on strike and complained about unsafe conditions at the worksite, but were assured by authorities and the architects that the bridge was sound.

The event was a major turning point for workplace safety in Australia, but at a huge cost: 35 lives and the lifelong trauma of the 18 workers who survived.

“Any person who goes to work should be able to go home to their family,” Antonietta said.

“There was the Royal Commission and people were held accountable, but I feel it shouldn’t have happened at all.”

The day of the disaster is still as raw as it was 50 years ago for Antonietta – and many of the other people affected – as it highlights the huge void left in her life by the loss of her father.

Antonietta often attends the ceremony held every year by the West Gate Bridge Memorial Committee to honour the victims, survivors and their families.

“I’m grateful to Danny Gardiner, Tommy Watson and everyone else for welcoming me into the West Gate Bridge family, which my father was part of,” she said.

“There’s such comfort in talking to people who are in the same situation.

“I’ve been fortunate to meet many men who worked with my father on the bridge and they’ve spoken so fondly of him.

“It’s made me feel emotionally saddened but also brought me such overwhelming comfort and peace.”

Anonietta hopes that by sharing her experience, she can remind Australians the men who died building the bridge that over 160,000 vehicles now cross every day.

“It’s a beautiful, spectacular bridge and it would be nice if every time people drive over it, they give thought to those who sacrificed their lives for us to have it,” she said.

“The bridge should also symbolise the message that life is precious and that we shouldn’t take anything for granted.”