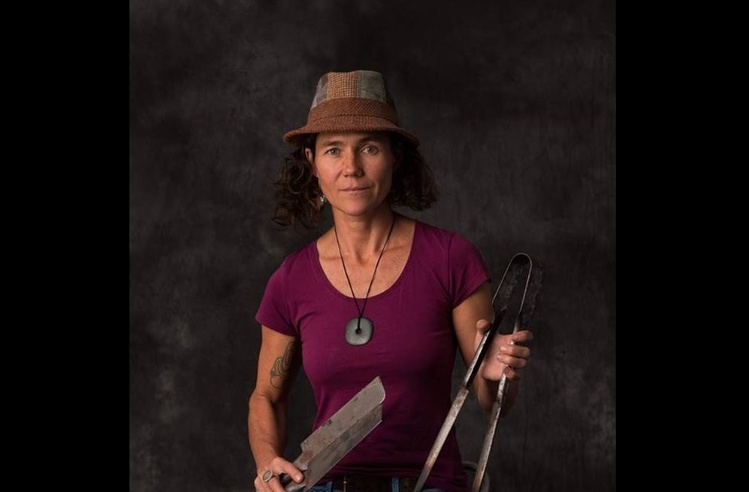

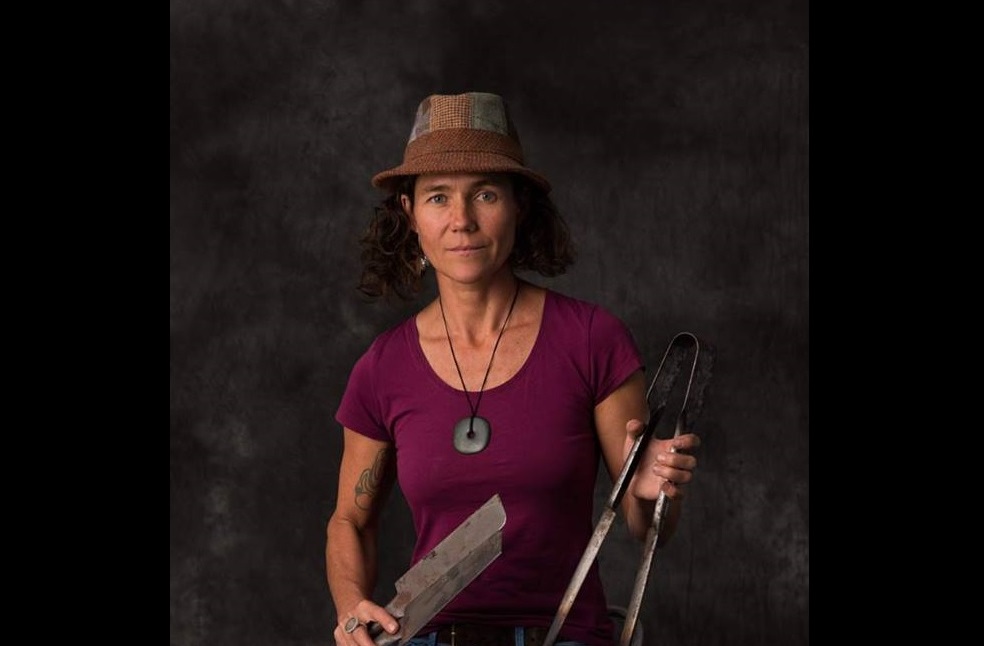

This weekend, Melbourne-based glass artist Ruth Allen will bring this age-old art to rural Victoria, at the Lost Trades Fair in Kyneton.

It may seem odd that a New Zealander residing in Australia is a skilled Venetian-taught glass blower, but Ruth has learnt from the best.

At 18 years of age, she undertook a glass blowing course in Whanganui, studying under Dante Marioni, an American glass artist who was one of the first to learn the Venetian technique outside the island of Murano itself.

“As I watched him work I realised that you could do anything with hot glass and it just had so much potential,” Ruth recalls.

“I decided that was what I was going to do with the rest of my life and I’ve been in pursuit of it ever since.”

Mariano was taught by Lino Tagliapietra, who was a pioneer of Venetian glass blowing and the first Venetian maestro to leave the island of Murano and spread the revered technique to America.

Having become a master of the craft aged 21 and worked at some of Murano’s most prestigious glasswork companies, Tagliapietra decided in the late 1970s that it was time for the rest of the world to learn the tricks of his trade.

Tagliapietra made history in more ways than one, sharing his skills with men and women alike (Murano glass was a craft once exclusively reserved for the men of the island), and regarding his work not only as a trade, but as an art form.

“Lino is so phenomenal in many respects because, not only did he decide that he was going to participate in a global movement, but he also looked upon the material as a beautiful medium for expressing himself,” Ruth says.

Not everybody shared Ruth’s enthusiasm towards Tagliapietra’s decision, and the glass artist was condemned by the Murano community for “leaking” their secret skills abroad.

He was banned from returning to Murano for a period of time for his apparent crime, which Ruth explains was once worthy of the death penalty.

Fortunately, Tagliapietra’s story has a happy ending.

Eventually, the revolutionary artist was allowed to return to his hometown and family, and his leaked techniques sparked the contemporary glass art movement which exploded during the late 1980s and the 1990s.

“Collectors were all over it and it was the most rapidly growing fine art medium in the world,” Ruth explains.

According to Ruth, the movement continued to escalate until the 2008 financial crisis struck, affecting the viability of many artists to continue to make a living off their work.

“It’s really expensive to blow glass; the infrastructure and what it costs to make is actually prohibitive unless you have quite a buoyant practice,” she says.

“If people stop buying, then you don’t have the ability to make.”

Ruth was one of the lucky artisans who managed to stay afloat during this difficult time, and she now works from her warehouse in Coburg North, where she has been based since 2010.

Ruth’s career as a glass artist has transported her around the world, and last year, she travelled to America to work with fellow glass blowers, including many Italians.

It was there that she discovered the dire situation on Murano, which has seen Venetian glass blowing become a dying trade.

“There are all of these artists on Murano who are exceptionally talented and are not getting the work because Venice is importing from China,” Ruth explains.

“They’re struggling and they’re not going to make it unless something happens.”

In an ironic twist of fate, it seems that the only thing that may save the industry is collaboration with artists abroad, something which Tagliapietra was once criticised for.

In fact, in 2018, the community of Murano will host the American Glass Arts Society’s annual conference, with Tagliapietra and his colleagues spearheading the event.

Ruth has already bought tickets, and will travel to Murano with her partner and 5-year-old daughter to partake in what she describes a “history-making” moment.

“All of those Italians who condemned Lino are now saying that they appreciate the ability to engage with the rest of the western world and foster collaboration and ideas, so much so, that they are prepared to hold the event on Murano,” she says.

In the meantime, Ruth will be attending the Lost Trades Fair, another event aimed to promote not one, but dozens of ancient trades which also face the imposing threat of modernity.

Ruth has participated in the event since its inception, and this will be her fourth year showcasing her trade.

Along with a colleague, Ruth will run a small-scale demonstration, showing visitors how her glass masterpieces come to life, and will offer people the opportunity to learn the techniques by signing up to her winter workshops.

“I think it’s important to educate people about different media, so that they can appreciate how things are made and understand their value,” she says.

Many of the courses in Victoria dedicated to glasswork no longer exist, and the course in Sydney is also on the cusp of shutting down, as the government is investing more into computer-based industries, such as architecture and infrastructure.

“The attitude is, if you can design it on a computer you can make it with a machine,” Ruth says.

“I find that so tragic and not true; you miss out on all the nuances of the handmade and you lose the skill.

“At least with workshops there’s an opportunity to share the experience with the public.”

Perhaps, through her involvement with the fair and her informative workshops, Ruth can spread her passion for glass blowing and ensure that the art lives on.

Could it be that Ruth is, in fact, the modern-day Lino Tagliapietra?

“Maybe I can be Lina,” she laughs.