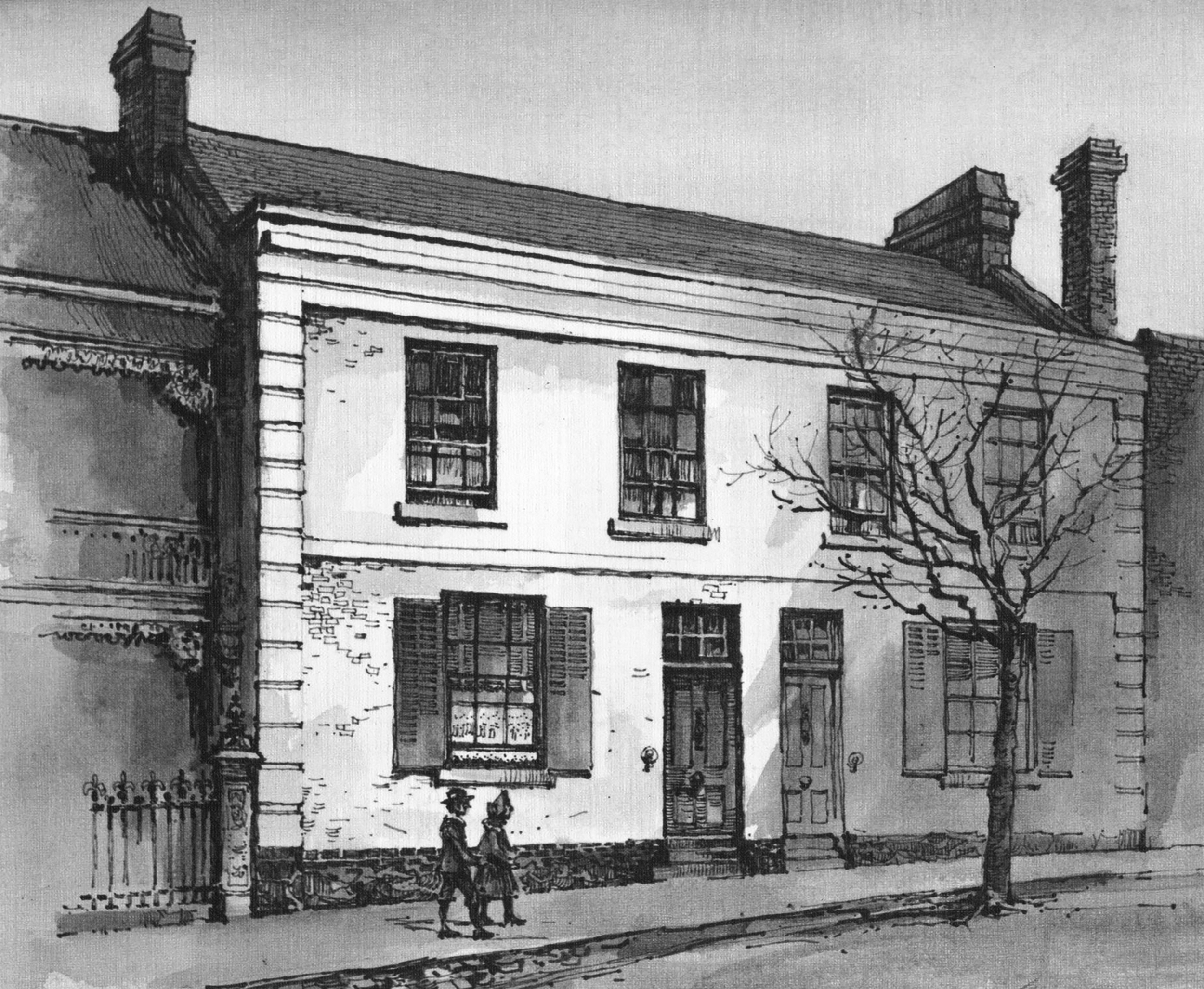

The hospital started out as a small house with just six rooms.

Today, it has more than 6000 staff across 12 wards containing 350 beds, and is one of the leading paediatric hospitals in the country.

The story of the RCH is one of visionary people whose tenacity and commitment have created an institution with a place in the hearts of many Australian families.

Originally named the Melbourne Free Hospital for Sick Children, the facility was located at what was then 39 Stephen Street (now 49 Exhibition Street).

The hospital was inaugurated on September 9, 1870, by doctors William Smith and John Singleton.

During its first year of operation, the hospital treated more than 1000 children.

The Melbourne Free Hospital for Sick Children

“In a century and a half, paediatric healthcare has advanced more than our forebears could ever have imagined, and The Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Melbourne has become one of the world’s great hospitals for children,”executive director of strategy, quality and improvement, Filomena Ciavarella, said.

“With a name synonymous with excellence and trust, and guided by leadership and compassion, the founding vision of the RCH continues today, enabling the hospital to remain at the forefront of paediatric healthcare and provide great healthcare everywhere, for free.”

In colonial times, Australian children were particularly vulnerable due to poor living conditions and hygiene, and there was a low life expectancy, especially for those living in industrial areas which were overpopulated and where health and food resources were scarce.

The RCH was inaugurated as a charitable facility where disadvantaged children could receive health care for free.

As the years went by, the hospital grew capable of caring for all children, regardless of their social class.

Six years after its opening, the headquarters were moved to Rathdowne Street in the suburb of Carlton; it was a larger building and contained 24 beds.

“Although Australia was free from most infectious disease for several decades after white settlement, when such illnesses arrived their severity was increased by the low immunity of the population,” Ciavarella said.

“Whooping cough, diphtheria, scarlet fever, dysentery, typhoid fever and measles all took a heavy toll on Australian children.”

The RCH has always focused on the future of medicine and the best possible treatments.

In fact, it was the first hospital in Melbourne to inaugurate a department of radiology, in 1897, under the guidance of Dr Herbert Hewlett.

This important step demonstrated the desire of the medical team to keep up with modern medicine, given that X-rays were discovered just two years earlier, in 1895.

In 1903, babies were admitted to the hospital for the first time, and by 1921, a whole new ward would be dedicated to babies, with a special physiotherapy gymnasium and treatment room.

The department was deemed necessary because many households were unable to refrigerate milk, forcing babies to drink milk that had expired or gone bad, which caused a dysentery epidemic in many patients.

In the 1930s, a 100-bed orthopaedic campus was opened in Mt Eliza to care for children suffering from tuberculosis, osteomyelitis and infantile paralysis.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the scourge of polio would see thousands of young people hospitalised for long periods.

But medical care at the hospital was rapidly evolving.

“In 1944, a nine-year-old patient named Allan Goates became the first at the hospital to receive penicillin from his doctor,” Ciavarella said.

“Then, in 1950, chemotherapy was used on children with leukaemia, the world’s first controlled trial of the drug.”

Among the most important milestones in the hospital’s history was the beginning of works on a new site, which started in 1948 but then discontinued due to a lack of government funding.

The structure was inaugurated and the first patient admitted on January 20, 1962, transferred from the Carlton building.

“Just 10 days later, on January 30, the hospital had admitted 152 patients with many more on the waiting list,” Ciavarella said.

She then recounted the major turning point with the opening of the new headquarters, which contained 400 beds and seven floors where each department boasted advanced technologies.

The new headquarters were officially inaugurated in 1963 by Queen Elizabeth during her visit to Australia with Prince Philip for the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Australian capital, Canberra.

The following years saw many developments in the medical field: in 1973, Dr Ruth Bishop identified the rotavirus, a genus of viruses known to be the main cause of childhood viral gastroenteritis in humans, that led to the hospitalisation of approximately 10,000 children each year; also in 1973, the first operation was performed for the division of two Siamese twins; and in 1988, the hospital undertook the first heart transplant on a child.

Dr Ruth Bishop

In 2011, Queen Elizabeth inaugurated the new campus of the RCH, situated at 50 Flemington Road, Parkville.

With six levels of clinical, research and education facilities the new RCH is a family-focused healing environment with improved accommodation for patients and their families, indoor and outdoor play areas – all surrounded by parklands and filled with natural light.

“For 150 years, the RCH has provided exceptional care to millions of children, young people and their families,” Ciavarella concluded.

“Treatments and cures for childhood illness and disease have been discovered, new and innovative models of care have been pioneered, and education and training have been provided to the world’s brightest medical minds.

“The story of how the RCH has grown from such humble beginnings to become one of the world’s great hospitals for children is as impressive as it is unique.

“The hospital’s anniversary recognises the extraordinary impact 150 years of care have had on the children of Victoria, Australia and across the world.

“It is an opportunity to acknowledge and thank the community, honour the hospital’s past and prepare for a future of bright possibility.”