At the time, the institution operated as the International School of Violin-Making in Cremona.

The school was established by royal ...

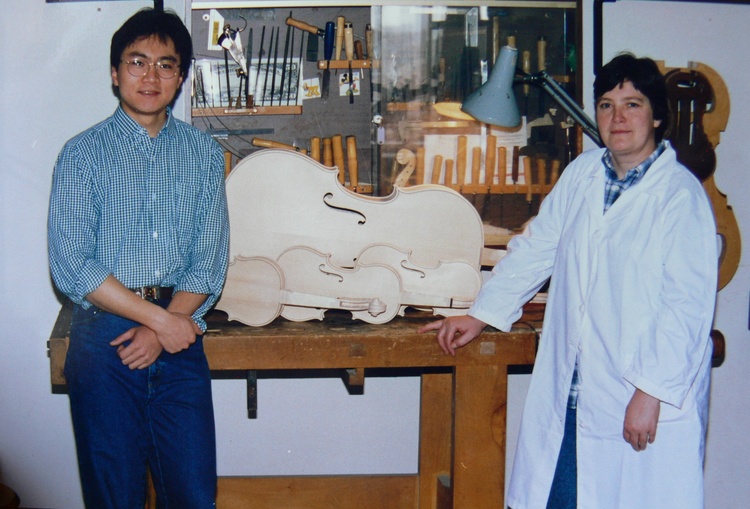

Wanna Zambelli was the first luthier – someone who makes stringed instruments – to graduate from what is now known as the Antonio Stradivari Institute of Higher Education.

Wanna Zambelli pictured with her pupil, GaoTong Tong, and a series of unpainted instruments. (Photos supplied)

At the time, the institution operated as the International School of Violin-Making in Cremona.

The school was established by royal ...