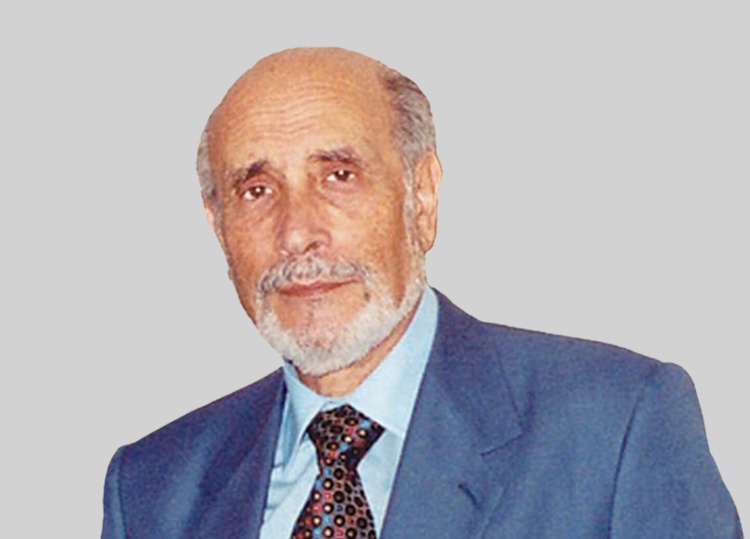

A journalist, writer, translator, essayist, playwright, historian and politician, Nino was always an important reference point for the Italian community in Australia, from his arrival in Melbourne in 1952, to his time as a Senator of the Italian Republic.

Nino was elected as a Senator for the overseas electorate of Africa, Asia, Oceania and Antarctica in 2006, at the age of 73 – when many begin to think about retiring, not reinventing themselves.

In an interview published in the Sydney Morning Herald the week after his arrival in Rome, Nino said: “I think [the role] will be challenging, rejuvenating and [it will be] very rewarding to be able to do something to further the interests of Italians abroad.”

Those who knew Nino could see, with every return visit to Melbourne, that his years in Rome truly did rejuvenate him.

Whenever he came to visit us at our Nicholson Street office, the same office he’d worked in for years, he always had a spring in his step.

Elected for the first time as a candidate for the centre-left coalition The Union (L’Unione), Nino was reelected in 2008 as Senator for the Democratic Party (PD).

Senator Francesco Giacobbe made a speech in honour of the late Nino Randazzo in the Italian Senate last Friday, which was followed by a moment of silence

Nino, who would’ve turned 87 next week, was born on July 22, 1932, in Leni, a town on the Aeolian Island of Salina.

In an interview with Aeolian journalist Antonio Brundu, he spoke about his arrival in Australia:

“I went to Australia in 1952. I stayed there for four years and then returned to Italy with the intention of not leaving again. But I began to miss the country I’d come to know and, in 1959, I returned to Australia. It was then that I had the chance to meet members of the Italian community and together we would give life to the newspaper Il Globo. This journalistic experience of mine was characterised by a very intense, satisfying and at times even exhausting work path; but it was very rewarding and gave my life true meaning. A life spent abroad, but always with Salina and the Aeolian Islands in my heart. That’s why, whenever I can, I make the ‘pilgrimage’ back to my roots: the Aeolian Islands, Salina, Val di Chiesa where I was born (and which is home to the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Terzito, who is worshipped by Aeolians across the world), and Malfa, the town where I grew up.”

During his many years in Australia, Nino never forgot his Sicilian homeland.

He settled in Melbourne with his wife Maria, who he met on the ship during the long journey to Australia, and they had three children.

Sadly, Maria also left us less than two months ago.

It’s likely that Nino’s already fragile heart couldn’t take the pain of this great loss.

Nino was the founder and first editor of Il Progresso Italo-Australiano, the official organ of the Italo-Australian Labour Council in Melbourne, and was a member of the the Labor Party’s Ripponlea branch, where he struck up a friendship with a young Barry Jones.

Following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, he joined the Democratic Labour Party (DLP), which existed from the 1955 split in the ALP, influenced by Bob Santamaria, an Italo-Australian intellectual who was a fervent catholic and anti-communist and Nino’s second cousin.

The DLP had a good relationship with the Italian community and, in 1964, in its first attempt to “exploit” the ethnic electorate, it put forward Nino as a candidate in the Victorian state election.

The seat of Fitzroy seemed ideal for this political experiment, but at the time many Italians hadn’t yet been naturalised and Nino wasn’t elected.

Nino later said he’d never contemplated being a political candidate in his adoptive home, because “a foreign name is a handicap in Australian politics, and very few have succeeded”.

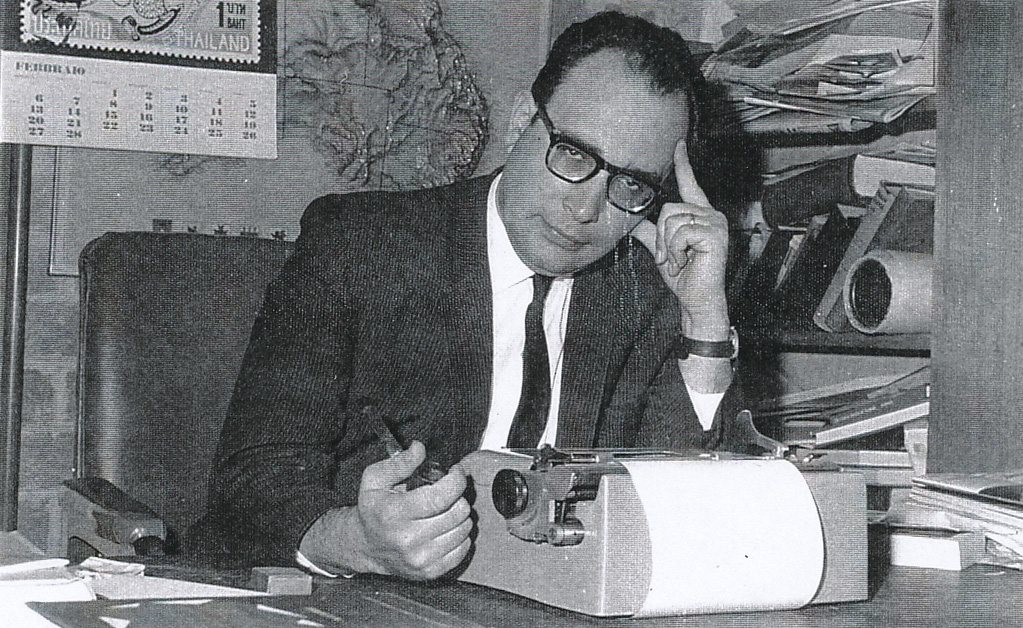

As a journalist, deputy editor and then, from 1978, editor-in-chief of Il Globo, Nino gained a considerable following of readers for his lively and often controversial writing style, and for his campaigns against attacks on the Italian community.

The first dates back to the early years of Il Globo, when the newspaper reported the weekly assaults on Italians and other news stories related to racism.

One such story was that of the “espresso bars of Melbourne, alleged illegal prostitution centres”, which occupied entire pages of the weekly in the first months of 1962.

Following articles published in The Herald, Channel 7’s Meet the Press interviewed a young woman of Irish origin, Jill, who claimed to have “been with 4000 Italians, 16 per night”, in the infamous espresso bars, provoking words of condemnation towards the entire Italian community.

All the journalists at Il Globo were determined to discover the truth, but it was Nino Randazzo who got the “scoop”, managing to track down the girl and reveal her real name: Billie Caddaye.

In a long interview, Caddaye retracted all of her statements, admitting that she’d received a payment of 10 pounds to make them.

In the article, a 30-year-old Randazzo wrote:

“We’ve discovered the true identity of the slanderer. Jill denies what she said on television under the pressure of police officers and journalists. The biggest scandal in the history of Australian television. The Herald and Channel 7 used the services of an Italo-Australian detective in the anti-Italian campaign. They brutally tormented the girl to make her repeat things she didn’t want to say.”

The story also had ramifications in the Parliament of Victoria: in the upper house, then Labor leader, John Galbally, highlighted the deliberate nature of racist attacks on one particular ethnic group.

The attention given to the story not only by Il Globo but also by English-language newspapers, undoubtedly contributed to putting the Italian newspaper in Melbourne on par with the so-called “mainstream” publications.

Nino Randazzo with his trusty typewriter, before the arrival of the computer

This first campaign was followed by many others, but the most symbolic was certainly that of 1977, which followed the murder of the chairman of the Liberals’ branch in Griffith (NSW) and anti-drugs crusader, Donald Mackay, who had exposed a gang of cannabis growers.

The investigations immediately focused on the Italian community, which was particularly large in the Riverina region at the time.

On July 25, Il Globo affirmed: “Mackay’s murderer is not among the Italians.”

In a series of articles, The Herald began to allude to “ties between Griffith and the mafia” and sent a correspondent to Platì, in Calabria, “to visit the places where the mafia live and die”.

This was immediately followed by a series of reports by Channel 9.

Il Globo didn’t feed into the “ridiculous generalisations about an entire town, founded on commonly-known and latent sentiments of racial hostility”, and denounced the “petty television reports that have offended the Italian community in Australia”.

That October, the Italian weekly sent an “open letter to the Channel 9 directors – for a more effective protest against the smear campaign of A Current Affair”, inviting Italians to cut the letter out of the paper and send it to Channel 9’s headquarters at 22 Bendigo Street, Richmond.

The protest lasted three weeks before Channel 9 responded, with a letter signed by President David J. Evans and executive producer of A Current Affair, Michael Schildberger, admitting their responsibility for disseminating information that was anything but correct.

The letter read: “On this occasion, unfortunately, in doing what we believed to be right, we have caused harm to innocent people for whom we have great regard.”

I met Nino in 1982, during preparations for a conference held in 1984, organised by the Victorian government with the participation of numerous Italian regional governments.

I’d already seen him on television, when he was interviewed by Mike Willesee for one of his campaigns against racism and prejudice towards our community.

Our professional relationship began in 1987, when I started working for Radio 3EA, at SBS, and I interviewed him on early mornings, when he was always wide awake and ready to talk.

With my colleague Umberto Martinengo, who also passed away too soon, I designed a ploy for our interviews with Nino: we’d ask him the first question and let him start talking away, then in the end we’d edit the interview and add in the rest of the questions.

A decade ago, I was asked to do some research into Il Globo’s 50-year history; it was then – reading his sleek, biting, and at times relentless and humorous articles – that I realised Nino’s contribution to the growth and development not only of our community, but of Australian society at large – a society which, thanks to his work and that of many others, has become a symbol of multiculturalism.

The combative Aeolian journalist applied the same elegant but direct writing style to his theatrical work.

To “relax”, Nino translated Manning Clark’s A History of Australia into Italian, wrote books and historical essays on the Italian community in Australia, and penned 16 plays, performed both in Australia and Italy.

These works often explored the ironic aspect of the migration experience.

In the Italo-Australian Theatre Company Inc’s profile, Nino wrote:

“The Italo-Australian theatre – a theatre that’s not only limited to staging classical and modern Italian works, but which also reflects aspects of the Italian reality in Australia following the migrant wave post-World War II – was first thought of in 1979 by the late professor Colin McCormick, unsurpassed Italophile and head of the Italian department at Melbourne University, who had already given life to a drama society made up of students from his department.”

Professor McCormick and Nino spoke one day in a casual meeting.

This first meeting was followed by others, and the concept began to develop until the former proposed that the latter write a play.

Thus came to light Il Pane e le rose, the “birth certificate” of the Italo-Australian Theatre Company Inc, which would soon be imitated in Melbourne and other parts of Australia.

Il Pane e le rose premiered in 1980 at Fitzroy’s Universal Theatre, as part of the Italian Arts Festival.

It was followed by many other titles, including Il Sindaco d’Australia, Victoria Market (whose English version was named one of the top six plays of 1986), Le Fiamme di Kalgoorlie and L’ultima flotta.

Past directors of the Italo-Australian Theatre Company Inc include: Franco Cavarra, who worked with the company for 12 years before finding his calling in the priesthood; Renato Cuocolo, the well-known Italo-Australian director who effectively traced a new artistic route for the company from 1991 to 1999, drawing on his personal experience and the passionate work of his predecessor; and, finally, the dynamic Maria Rita Sanciolo-Bell.

With L’ultima flotta (1989), Randazzo, abandoned the theme of social realism and presented instead a highly pessimistic view of the future of multiculturalism in Australia.

Set in 2020, the play features a group of elderly Italians who arrived in Australia in the 1970s and who, after half a century, must fight for the cultural survival of the Italo-Australian community in a society which has abolished multiculturalism and become profoundly racist and xenophobic.

In his fanciful prophecy, Nino may actually have been surprisingly accurate; perhaps he chose to leave us now so that he wouldn’t have to face that world.